[Earlier this month we brought you a potted history of pop-culture’s obsession with the concept of tsunami surfing; spanning appearances in old Hawaiian folklore, through TV ads and Hollywood cult classics, to an alleged feature in one of youtube’s first viral videos.

Here, we’ll tell the story of a big wave legend and early surfing world champ who claims to have surfed a tsunami.]

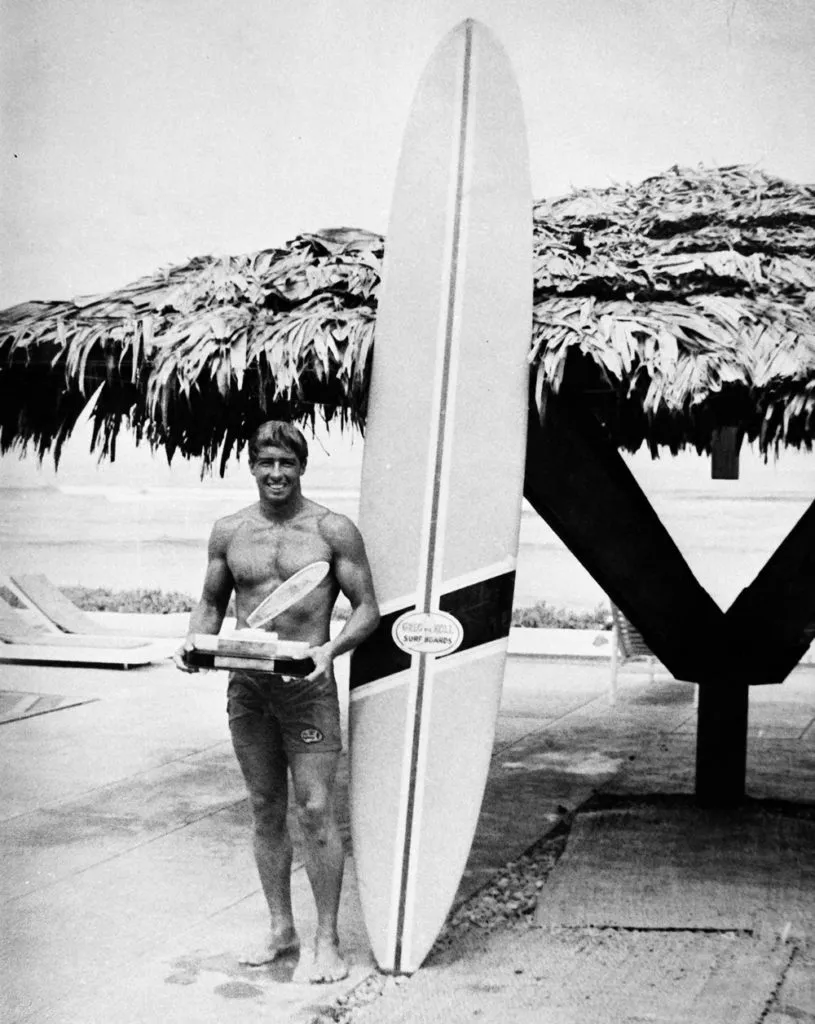

Felipe Pomar was born in Peru in 1943 and learnt to surf in the waves around Lima in his early teens. When he was 20, he moved across the South Pacific and settled in Hawaii, where he soon took his place among the top local big wave riders. Over the proceeding 5 years he picked up a slew of impressive results in both Hawaii and Peru, including a World Championship win in 65 and a series of podium finishes at the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational, held at sizey Sunset Beach.

When it comes to his legacy, however, these accolades serve as mere footnotes to his unwitting involvement in the events of October 3rd, 1974.

Felipe was back in Peru for the season, staying with his friend Piti Block in the coastal town of Punta Hermosa where he hoped to score some solid surf while the north shore slumbered.

“We had reason to believe that a wave in Peru called Pico Alto got as big or bigger than Waimea,” says Felipe in an interview with Swellnet, “and I was looking to find as big of a wave as I could.”

However, on that grey Wednesday morning Felipe awoke to find the waves were about as small as they ever got. “It was maybe shoulder to head high,” he remembers. “Which in Peru is considered flat.”

Nonetheless, the boys were on a strict training programme, so they suited it up and headed for a break called ‘Isla’, host to a series of peaks that form in the shadow of a large rocky outcrop, which extends out for almost half a mile. They were just about to step down onto the sand when Piti suddenly began yelling and gesticulating wildly in the direction of the craggy peninsula.

Felipe was aghast. “I’d known this person for 15 or 20 years, and I’d never heard him raise his voice,” he remembers. Piti was a race car driver and a big wave surfer of some note, not prone to bouts of hysteria.

Following his friend’s gaze, Felipe spotted a group of people perched on top of the island doing what looked like a sort of chaotic dance.

“Then all of a sudden, I heard this amazing sound,” Felipe tells Scott Mijaris on Kuai community radio, “like a train or a jet engine all of a sudden was upon us. But there was nothing there.” Shortly after, the ground began to shake violently. Piti immediately turned and ran, leaving Felipe alone to contemplate the tumult.

As the walls of the town began to crumble around him, he remembers clinging to his surfboard in the hope it would act as an anchor, should the ground beneath him suddenly crack open and attempt to swallow him up.

After almost two minutes, the quake finally subsided and Felipe set off into the town’s narrow streets to find his friend. Once reunited, the pair contemplated what to do next. They quickly concluded driving anywhere would be far too dangerous, because of damage that had likely been caused, so Felipe offered up an alternative.

“Considering we had our wetsuits on, we had our surfboards under our arm, you know, I said, ‘let’s go surfing!’” he recounts.

“Now between you and I, I expected him to say ‘you’re crazy’ and I would have accepted that, but instead he said ‘ok!’”

“I thought after this pretty amazing earthquake, there’s bound to be some waves, so what kind of waves could they be?”

“I had lived in Hawaii for about ten years and I had heard a lot of tsunami alerts and none of them had generated anything impressive. You know there had been some, a few inches here, a few feet there, and so in my mind I thought it could generate ten foot waves…or maybe it could even generate twenty foot waves.”

“I felt totally capable of surfing what today are called 30-40 foot waves. I mean I was certainly experienced, I was in top physical condition, I was young, I thought I was bulletproof, I thought great, we’ll get some big waves and we’ll ride them.”

To Felipe’s disappointment, when they commenced the paddle to Isla, they found the waves were still small and gutless. Peti was the first to get to his feet.

“No sooner had we got out that Piti paddles up to me and says he wants to go in,” remembers Felipe. “I told him we’d just got out. ‘Why would you want to go in?’. And he said, ‘Well, I just caught a little wave and it held me under longer than I’ve ever been held under in my life. So I want to go in.’”

Reluctantly, Felipe agreed to catch one in. As he sat, scanning the horizon, he noticed a strong current had kicked up out of nowhere and was dragging them out to sea.

“So now I start paddling as hard as I can, and I don’t want to look [at the shore], because I’m concerned now; I can’t go any faster than this and If i’m going backwards now I have some serious problems…”

“Eventually I had to look, and when I turned, I saw I was going back so fast that there was no sense in paddling at all.” Felipe sat up on his board and began some deep breathing exercises. “I figured ok, relax, because you’re going to have to make some important decisions.”

As they drifted further out, the pair became surrounded by huge boils and whirlpools bubbling off the bottom as well as 6-foot side chops that seemed to be coming from all directions simultaneously.

As they watched the vast mainland, with its layers of misty mountain peaks, recede into the distance, Felipe remembers feeling a profound sense of insignificance. “It was like you were smaller than a grain of sand,” he says.

Even more frightening was the idea of what might still be yet to come. The force and speed with which they were being dragged out had led Felipe to reassess his earlier prediction, forged with bravado on the safety of dry land, as to the possible size of the waves the tremor would create.

“Under the circumstances, I thought [the tsunami] could be a hundred feet….and I realised we were in deep trouble,” he says.

In that instant, Felipe decided their best bet was to paddle to a deepwater reef named Kon Tiki, located about a mile away at the southern end of the bay. The plan was to try and catch a wave from way out the back into the shallower waters near the shore, and then paddle the remaining distance back to the beach.

After around half an hour of frantic paddling, with one eye trained on the horizon at all times, the pair made it to within scratching distance of the reef.

“It was the first time something positive was happening,” says Felipe. “I stopped, and when Piti got close to me I told him what the plan was.”

“Paddle into the impact zone, catch the first wave that comes by- or let it catch you, take it as far as you can and I’ll see you on the beach.”

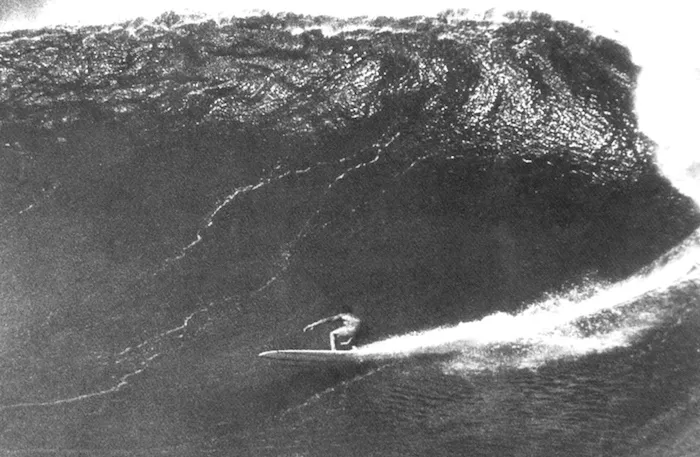

“Then we started paddling again, I got into the area, and all of a sudden there was a wave there, I paddled really hard, I picked it up, and what do you do when you pick up a wave? I jumped to my feet and I turned.”

“It was a big wave- bigger than a house; it was not 200 feet- it was not the tsunami I was expecting, but it was a big wave. When I turned I thought what are you doing, you’re not supposed to be surfing! You’re supposed to make a bee-line for shore! And then I had a second thought which was you may not make it to shore, this may be the last wave you ever catch, so you might as well enjoy it and I remember making a bunch of turns on it! [laughs]”

When the wave broke, Felipe dropped into a prone position and did his best to hold on as the white water galloped shorewards. As the energy dissipated, he began to paddle once again, throwing a quick glance over his shoulder to check if the giant wave had presented itself yet. Still, he saw nothing, so he returned his gaze towards the land and was relieved to see it finally seemed to be getting closer. Then, off to his right, something caught his attention. In the distance a rogue wave had picked up a fishing boat and flung it into the cliff face, shattering it into a thousand splintered pieces.

“That shocked me,” he remembers. “Because I was expecting a big wave on the horizon and now all of a sudden out in front of me there’s these flying boats!”

“But I decided I wasn’t going to think about that, because I had to focus on getting myself to the beach.”

After several more frantic paddle strokes, Felipe hopped off his board and sunk his feet into the sand. As he looked back towards the reef, he saw Piti too was just a short way from safety.

“We were so happy we danced and hugged each other and slapped each other on the back, I mean what an amazing experience, first the earthquake and then getting pulled out to sea and then riding these waves and making it back to shore. That was amazing.”

The pair didn’t tell anyone about the experience for many years, out of respect for the hundreds of people killed by the earthquake.

In the years since the story was first published, he’s had to defend the account from numerous detractors within the academic community.

“The scientists’ argument regarding the impossibility of “riding a tsunami” is, I believe, a purely semantic one,” he summarised in The Surfers Journal.

“Were those waves “tsunami” waves or “indicator” waves, or some other kind of wave? I don’t know. But I know they weren’t meteorologically generated. They weren’t created by atmospheric phenomena. They were clearly generated by a seismic event—a planetary episode. The experts can call them whatever they want, but like many naturally occurring anomalies, those waves did not conveniently fit any existing scientific model.”