Jeff Martin’s flight had only just landed in Munich when he made time for us to chat the Yulex story. As a founder and CEO, it’s a transformative tale of shifting the wetsuit industry off petrochemicals and towards plant-based rubber. And this tale has a surprising catalyst.

*This interview is part of a series on Wavelength, lifting the lid on the stories behind the brands we use every day in surfing.*

Thanks for talking with me, Jeff. Can we start by exploring the origin of Yulex. What’s your background, and where did the idea come from?

It goes back more than ten years ago when my partner and I, my chief technology officer at the time, read an article by Patagonia. It referred to the new limestone neoprene that had come out, and they considered it greenwashing. So they put out a piece that said, ‘There’s no such thing as green neoprene‘. I’ve been working with natural rubber all my life in medical and consumer applications and all kinds of applications from agriculture to finished products. So Jim Mitchell and I, my chief technology officer, said, “You know, I think we could replace chloroprene rubber with natural rubber and make a green neoprene.“

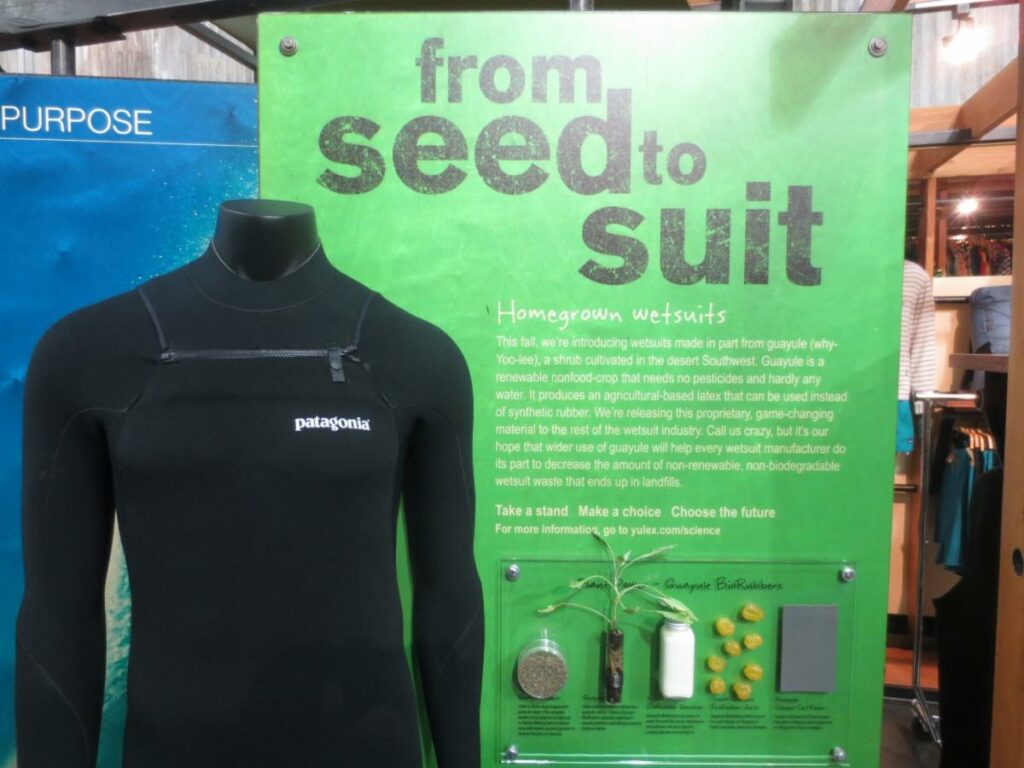

We had already developed an alternative source of natural rubber in Phoneix, Arizona, called guayule, which is grown from a plant initially indigenous to Mexico. And to cut a long story short, we used this to create lab samples of foam, a closed-cell foam that we thought had similar properties to neoprene and called up Patagonia, spoke to the individual who put up the blog and set up a meeting. They were pretty excited about what we had invented and set up a much larger meeting a couple of weeks later; Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, was there as well, and that’s where it all started – they just loved the concept – and we were off and running.

That’s a great origin story. I remember attending the Euro launch of the guayule wetsuits in San Sebastian many moons ago, and at the time, we didn’t fully appreciate the broader context. More recently, I’ve been working with natural rubber in footwear and love it as a unique natural material. Out of interest, have you looked at dandelion latex as a future material in wetsuits?

Absolutely. Yeah, so we’re in very close communications with all the technologies and companies involved in alternative sources of natural rubber. I happen to sit on the advisory board of a company in Canada that has been developing TKS or Russian dandelion rubber for years. I would say that it’s also an excellent alternative source of natural rubber, and it’s functionally the same polymer produced by the plant, whether it’s from the Brazilian rubber tree, guayule, TKS, or quite a few others. Thousands of plants make natural rubber; when you strip them down and remove all the unnecessary materials, they’re all very good natural rubbers.

I can’t stop dandelions from growing in my garden, and I imagine there are areas of less productive land where there’d be room for plantations. I assume that the same is true with guayule?

Yes, it all comes down to how much rubber you can produce per acre or per hectare for it to be economically viable. The yield is there with guayule and it is currently being scaled up in Southern Europe for commercial use and in the U.S.

One day, guayule will be a large part of the world economy, and it actually found its first commercial use in wetsuits. It’s being developed by the biggest tire company in the world, along with a huge synthetic rubber company that is also looking for a natural alternative. So it will be pretty large, and it all began in surf which is pretty cool.

That’s something to be proud of as an industry. Do you surf yourself?

Absolutely. I do surf, but not much… I don’t consider myself a surfer. We do, however, dive quite a bit.

As they say, you’re an overnight success after a lifetime of work. For a time, it was just Patagonia using Yulex in wetsuits, then Finisterre, and now it seems like everyone is ditching neoprene. Oxbow, Billabong, Need, Srface etc. Xcel have promised to move their entire range by 2026. As someone who works in surf and footwear, this gives me hope to see pivotal change in an entrenched industry. Are you surprised by how quickly the whole industry has moved?

No, I was not surprised. I thought it would shift earlier. I’ve seen industries shift, and I’ve seen industries shift in very large ways, so I was surprised that they didn’t move earlier. But it is shifting now, that’s very positive. And as you said, I can’t think of any major surf brands that are not evaluating or committed to moving over to natural rubber. I think all the major wetsuit companies will move to include it in their product line. It’s just a question of which ones start to convert the majority of their lines to natural rubber from chloroprene or SBR. And I think that’ll simply be based on performance.

Yulex used to have a reputation for being a little stiff, but that isn’t the case anymore. How have you managed to make it more flexible?

Yeah, there are two answers to that. First of all, let me state my background. I’m a materials engineer, and I’ve worked in polymer science for a few decades. So there’s no reason that natural rubber cannot perform equal to or better than chloroprene rubber in just about all areas, with the exception of a couple that I’ll name. It was always disappointing that the biggest issue with Yulex rubber was that people would say it’s not stretchy or warm. And frankly, when you compare the basic characteristics of natural rubber to chloroprene rubber, that shouldn’t be the case if you understand the science and the physical properties.

We had Yulex being manufactured by just one manufacturer for many years. Since introducing the material to Patagonia in the U.S., just one manufacturer, Sheico, has been manufacturing the material. Whilst we had developed some variations of the closed cell in our labs, which were very flexible and warm, we could never really enter into the type of technical partnership with Sheico to improve the Yulex formulation. So keep in mind that companies have been working with chloroprene rubber and SBR for decades with continual improvements season after season, year after year. Yet, after Yulex came on the market and Sheico was the only manufacturer, frankly, it may not have been in their best interest to improve the material. It sat, if you will, on the bottom shelf without any real technical improvement or promotion. And many people in the industry didn’t want to see a natural rubber material that would be equal to or better than chloroprene because it was an existing industry that was hard to move and change habits. As you said earlier, this is the same in many industries.

So, a couple of years ago at Yulex, we got a little frustrated and decided to develop our own supply chain, and then we went out to the market. And as you may know, Liz and I have been living in Asia for the last two years. We just returned last month. We have been developing a new supply chain, new plantations for natural rubber, new manufacturers for the foam, and wetsuit manufacturers. We developed a brand new supply chain for our closed-cell foam, not only for the surf industry but also for applications in footwear and accessories, sports, medicine, and a number of other applications that could use a replacement for neoprene.

And that’s when we started to see the changes. All of a sudden, we saw much better products coming out of Sheico. Patagonia got better products, Billabong got better products, Finisterre got better products. It was a combination of both improving the foam and, as you probably know, a big factor is the fabrics that are laminated to the foam. So, if you have a great foam but a poor-performing knit fabric, that will override the great properties you will see in the foam. So those improvements were made, and now we’re starting to see the true colours of natural rubber.

That makes sense because, having used natural rubber in footwear manufacturing, I could never understand the negative results in wetsuits. Planes need natural rubber tyres to land; the material is stretchier and has a higher tensile strength than artificial rubber. So, I could never understand why Yulex was worse. Thanks for clearing it up.

Yeah, that’s exactly right. We’ll have to wait until the new products come out, but we’ll make much better wetsuit products from natural rubber than those made with chloroprene rubber. So you’ll see much better improvements, and as you already stated, we could do much more with natural rubber. There’s already so much known about its properties, and we’ll reinvent it for the wetsuit industry.

There’s still an element of artificial rubber in some Yulex I see on the market?

Yes, so right now the suits are 85% natural rubber. There is 15% synthetic rubber in there, but you should see that removed over the next couple of years with the new iterations. As a matter of fact, Decathlon has announced they’re gonna come out with a UX 100 suit. I’m not sure if you saw that. And the 15% I mentioned earlier in the conversation that one of the properties of natural rubber that is not as good as chloroprene rubber is ozone resistance, so synthetic rubber is added for that reason.

Still, there are other ways to achieve that without adding synthetic rubber and in the next one to two years, most formulations will eliminate the synthetic element. Remember when we started out with Patagonia? The first suit was only 60% natural rubber, and we now have additives that we can put in that are environmentally friendly, non-toxic, and provide ozone resistance.

Another idea is Yulex is expensive, but with Decathlon using it, they are proving that you must be able to do it for the right price?

When you’re talking about price, keep in mind the process for making the foam. We like to change the chemistry of materials and drop them into existing manufacturing equipment to scale up rapidly. So, having said that the only difference in price between our closed-cell foam and neoprene closed-cell foam is the raw material, and the raw material for natural rubber is considerably less expensive than chloroprene rubber. So, as we enter the marketplace you will see Shieco dropping its price considerably. We have a new supply chain that is now beginning to manufacture in China and soon after Vietnam, and the price points will be equal to or less than neoprene.

Setting up a new manufacturing process is a huge commitment. But you have done it because of the market limitations of being beholden to somebody else?

Well, first of all, everyone that’s in the industry right now is making a natural rubber and foam and its all U.S. technology. For example, Xcel is going into the market with the Nam Liong natural rubber. Well, that’s our technology. Yulex made several trips to Taiwan, and we met on many occasions. We probably had 50 to 75 trials to transfer the technology and teach them how to make closed-cell foam with natural rubber instead of chloroprene.

So the first wetsuits were made by Nam Liong, not Shieco. Then, Patagonia made a decision as they were scaling up: they wanted to move their business to Shieco, and then we taught them how to make natural rubber foam. So we transferred that technology to both of them.

There are a couple of other players out there. Wellpower in China uses U.S. technology, and there’s also a smaller company in Japan. They still need to launch it, so I won’t mention their name. But it’s not Yamamoto. I think pretty much everyone that’s out there has used our tech. We showed all the companies in the industry how to do it, and of course, we also developed the concept, not just the technology, for replacing neoprene.

Another question I often see relates to the availability of natural rubber in the supply chain and deforestation.

As they say, our concern had always been to not jump from the frying pan into the fire. You don’t want to move from synthetic technology and then to move into a natural rubber industry where there’s problems as well. There have always been problems in the natural rubber industry.

So one of the concepts we took to Patagonia when we started this up was we wanted them to be aware of the issues in natural rubber and to ensure that they’d only use certified supply chains. So, we started out with FSC 10 years ago. No one in the consumer product industry was using certified natural rubber supply chains. We could trace it all the way back to the plantation and ensure there was no deforestation, human rights violations, chemicals, etc. So, we brought that supply chain to Patagonia. They endorsed it, and over the last decade, certified traceable supply chains have become quite popular and will now be required under E.U. regulations. So, for any product with natural rubber that’s used in Europe, it has to be traceable if you’re going to import or export natural rubber. So, certification is one way of understanding traceability.

We also brought the certified supply chains to the surf industry and offered our supply chain to Shieco. They can use other supply chains, of course, but they’ll have the U.S. supply chain available. And then, of course, we now have our own supply chain. So we have our own manufacturers of the foam and our own wetsuit finished product manufacturers. Partners. Authorised manufacturing partners throughout Asia, and that are currently making suits. We’re actually manufacturing and gearing up right now and with several of the major brands that are evaluating the new Yulex supply line.

As we wrap this interesting chat up, I wanted to ask you about circularity in wetsuit manufacturing; we are still quite a way off being able to turn old Yulex into new yulex. What would you describe your vision for the perfect circular wetsuit?

Well, when I think about circularity, I think about wetsuits and sometimes I’ll put them in the same bucket with footwear and that they’re not designed to be disassembled. So when you’re taking many different materials, when you’re taking nylon, polyester, spandex, neoprene, and or rubber, and you’re bonding them all together with heat or adhesives, and then you want to put them in a landfill, you know, or an industrial composting facility or you want to grind them up and reuse them, well you really can’t do that until we do a much better job with design.

We’re making much better progress in circularity with the reuse and recycling of materials, but the design is holding us back. So, for instance, with the wetsuits, there’s a couple of things that I’ve seen, and I’ll tell you what our approach is, but first of all, you see the regrind, you see the grinding of a wetsuit. So, to me, that’s downcycling. I don’t think that’s going to prove to be cost-efficient because the value of their products is going to be less than the virgin material if you will, and to collect those materials and to transport them and to pull the zippers out and to grind them and to put more different material in there looks cool. But still, I don’t think it’s going to be an efficient process.

There are a few companies that are using a process called pyrolysis, I don’t know if you’re familiar with that?

It’s a superheating process, isn’t it?

That’s right. And they can convert it to carbon black, an ingredient in rubber wetsuits. Whether it’s chloroprene rubber or natural rubber, you can use carbon black as a pigment or, as what they call, a filler or a reinforcing filler in the material. So that’s another use for it.

At Yulex have a bio-based material, and natural rubber is known to be biodegradable, but of course, we only make the foam. The wetsuit manufacturers select fabrics and laminations to make the finished product, so keep in mind we don’t have a lot of control over the other materials that go into it and how they’re finished and how the product is made. Our supply chain goes all the way back to the plantation, but it stops at the foam manufacturing.

I completely understand that, and it’s the glue. It’s the fabrics you’re sticking it to and what we really do need is a new glue that doesn’t fall apart until you want it to deconstruct itself and then becomes environmentally inert. But I don’t know whether that glue in on the horizon yet.

That’s kind of the rub. Everybody wants something ideally durable that will last almost forever until you want to stop using it. And then we want to take that wetsuit, or that pair of shoes off, and to have them biodegrade and dissolved in three days. I’m being facetious, but that’s the ideal. So yeah, it’s not that simple. If you design for durability, it’s gonna be durable, I’ll give you an example: natural rubber. So, for instance, you can use natural rubber to make chewing gum. And it’s very soft and chewy, obviously, and the properties are not very demanding, and it will biodegrade in weeks to, you know, a couple of months, it’ll be gone completely.

But if you were to use natural rubber to make, as you remarked earlier an aeroplane tire, you put that tire in a landfill and dig it up, many, many, many, many years later, that tire will still be there. So it depends upon the chemistry you add to the raw material, which will also affect its degradation properties. So you can design it to be durable or not, and the mindset of many companies is to design something to be durable.

And to finish off, one final brief word on limestone neoprene… Greenwashing or not?

On the limestone? Yes, so I mean it is. Also, it depends upon who’s doing the advertising, so I can only talk for part of the industry. Still, we’ve done quite a bit of analysis on the carbon emissions of different materials used to make neoprene rubber. So whether it’s oil-based to make butadiene or limestone-based to make butadiene, they’re both very large carbon emitters; frankly, the limestone emits more carbon than the petroleum.

So, from a carbon emission standpoint, it’s not greener at all. Limestone has been used to make neoprene for many, many years. There’s nothing new to that. I think the industry got a hold of it and said, “Hey, this is great. We’re in water sports. This is made from limestone. Isn’t that like sea shells?” So everybody had this image of people walking around collecting shells off the beach and making wetsuits.

Essentially, it is a pretty nasty mining operation where if you’ve seen pictures of mining, it’s a very intensive operation.

And just so you know, if you were to refer to our website, Liz Bootbouy, our CEO, has put together many of what’s called rubber chronicles, and you can find them under, resources and it has the carbon footprint of neoprene and limestone, and provides specific data on that if you’re interested in looking at that.

Thanks Jeff, that was super interesting; we appreciate you taking the time.

We do appreciate your interest; you had great questions, and I’m glad you’re quite knowledgeable about the area, which helps the interview a lot, so we appreciate that.

No problem, there’s so much noise out there on the internet and hopefully things like this will help the consumer understand their product a little bit better. The E.U. has just started to try and regulate marketing greenwash but really, there’s been no effective regulation until now.

I think we’re in the beginning stages of scrutinising advertising claims and greenwashing, and not that we expect the customers to thoroughly understand all the different technologies for many different products that are out there, but at least the new greenwashing regulations will make companies think differently about how they brand their products.

Hopefully! I suspect we’ll need a couple of court cases first, and then companies will start thinking about their environmental claims.

Want to get your hands on a fresh copy of #265? Wavelength gets delivered straight to your door either as a single edition or annual subscription.