The life and times of Art Brewer.

Words: Dibi Fletcher Photos: Art Brewer

It seems like another lifetime, that fateful winter of 1969, when Art Brewer moved into the house next door to Herb and I on the North Shore. After barely escaping with our sanity from Laguna Canyon and our escapades with the now infamous Brotherhood of Eternal Love, we were living a quiet life.

We had breathed a sigh of relief to be back in our home on the beach at Pupukea, when John Severson, the founder and publisher of Surfer magazine rented the house next door. Not only did he move in with his wife and kids, he also had Art, a hot, young photographer who had just landed his first Surfer cover, and Spider Wells, a cinematographer, sharing a room too. Immediately, it seemed that their collective intent was to chronicle life on the North Shore, like it or not.

Aside from being the owner of Surfer, Severson was a good friend of my dad, Walter Hoffman, big wave rider and fabric icon, which complicated matters even further. With Art climbing around the bushes between the houses to catch candid shots for an ‘A Day in the Life’ story, things got a bit strained. However, life on the North Shore always has a way of taking a back seat when the ocean comes alive.

We awoke before sunrise on a wintery day in December to the thundering of waves crashing so hard on the beach that the houses shuddered. We ran next door to get a better view from the porch and what we saw was heart-wrenching. The waves were coming up the beach like grasping fingers, smashing and pulling anything in their path out to sea. Herb and I ran out back and jumped into our rusted-out VW bug. With Art in tow, we headed up Pupukea hill to get a better view. We got out of the car at the top of the hill and looked out towards the horizon, it was all white water, as far as we could see. In all the years Herb and I had been coming to Hawaii, we had never seen anything like it. The shots from that winter would change the ‘surf story’ forever. Up until that time, most commercial shots for the new, burgeoning surf press were focused on the more playful side of Malibu ‘Moondoggie’ and Beach Blanket Bingo fun-in-the-sun characterisations. Now the waves, the fearless breed of extreme thrill-seekers who would ride them and the genius in the eye of the photographers who would capture the madness would set the stage for what, in the minds of many, would be the glory days of surf photography.

The group of hard charging North Shore surfers were less than thrilled to have their more personal moments captured, even though those are often the shots that build the narrative that storytellers know can make an article come to life. With the threat of being severely beaten, anyone with a camera knew to keep their distance. Herb’s introductions gave Art the entry to the characters who he would capture during that winter of winters. He landed another cover and numerous spreads which made him the most sought-after still photographer in the, then small, field of surf photographers.

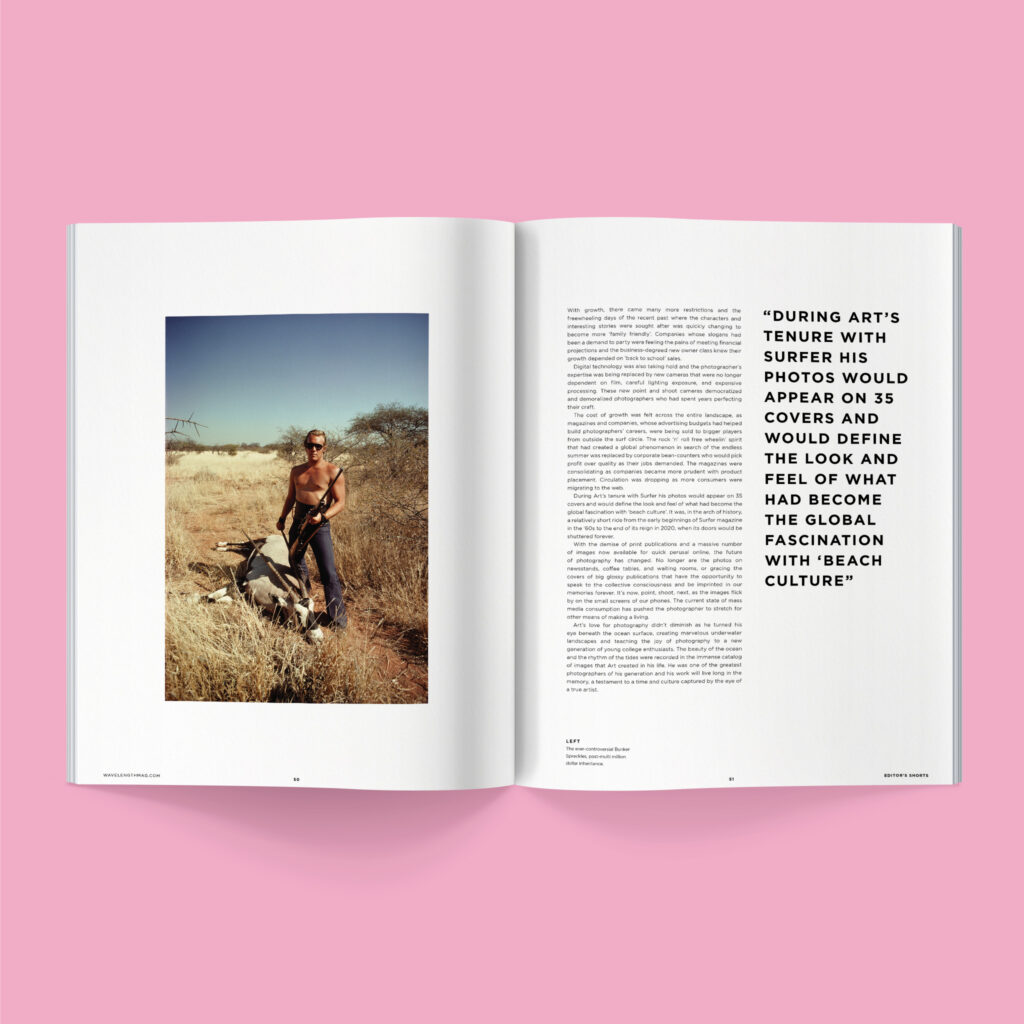

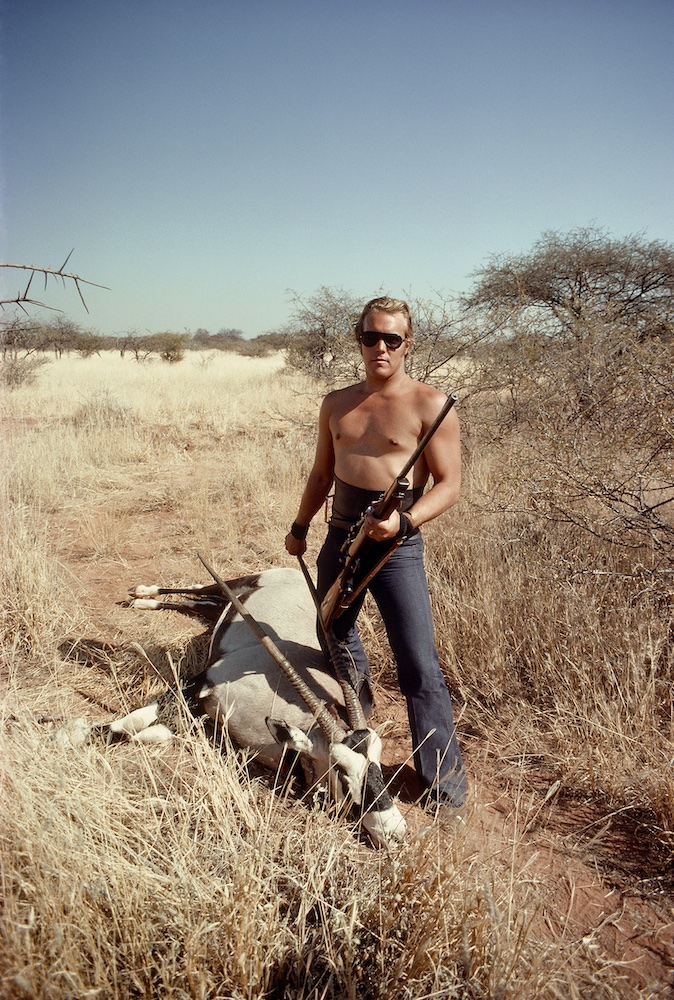

It was during this time that Art met Bunker Spreckels, the heir to the Spreckels sugar fortune and stepson to Clark Gable. On Bunker’s 21st birthday, in 1970, he inherited the family fortune and would embark on a six-year, drug-fueled odyssey that Art was hired to intermittently tag along on and document. In ’74, they traveled from Los Angeles to London, South Africa and Paris with one rule that Art had to follow. ‘If I was fired, I’d receive a first-class ticket home. If I quit, I was on my own. No salary, but all expenses paid.’ The party continued until Bunker’s untimely death in ’77 at the age of 27. The photos and film captured in those tempestuous years were later documented in a book, Bunker Spreckels: Surfing’s Divine Prince of Decadence that Art collaborated on with C.R. Stecyk lll.

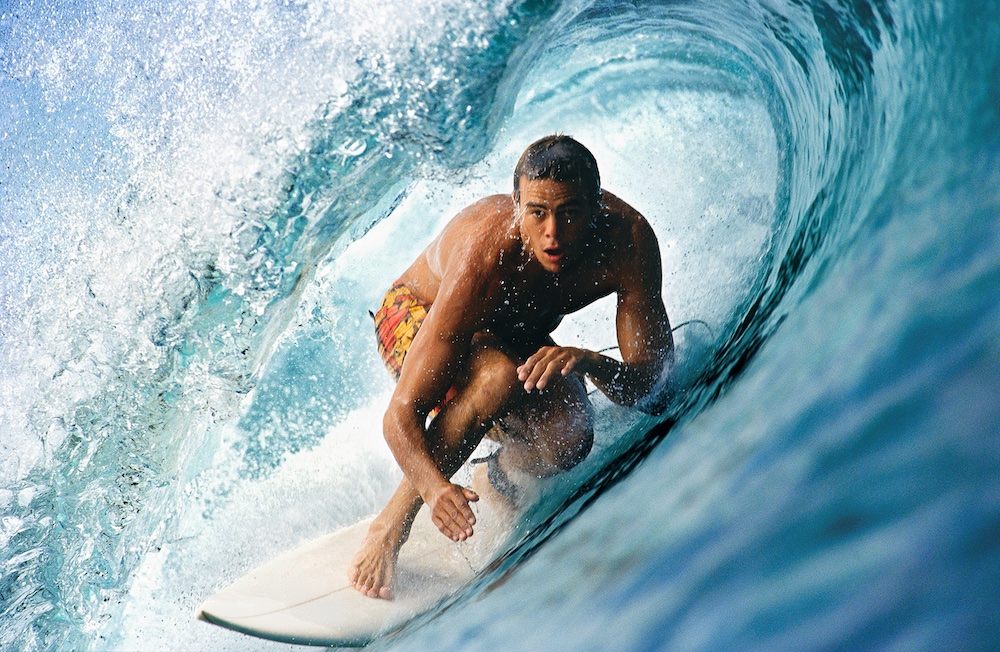

With the growing ‘industry’ and a need for more exotic locals for content and commercial shoots, the relationships between surfers, photographers, companies and the magazines took on a unique sort of love/hate dysfunction that fueled the ever-growing popularity of surf culture on the global stage. Art’s images would stare out at you from newsstands, sit on coffee tables, and be carried in backpacks to the local high school to be shared and awed at over lunch. His vast body of work was the imagery that defined a generation.

Many of the larger clothing companies started adding boat trips to the advertising budgets, and that’s when the skill of cat-wrangling was added to the list of abilities required of the photographer. Art was pretty well-equipped to handle an unruly bunch of young Turks with his acerbic wit and fine-tuned BS barometer. Photos of the greatest tube riding aerial masters of the late ‘90s, in the pristine waters of the Indian Ocean, were splashed across the glossy pages of magazines which bulged with ads pushing young consumers to buy, buy, buy and grow the ever-expanding industrial complex.

The beauty of Art’s images didn’t go unnoticed by Madison Avenue and he was soon shooting for many of the popular mainstream periodicals. Some wanted their bit of Beach Blanket Bingo and Art had a who’s who rolodex to choose from. He always enjoyed shooting me and Herb and the boys, Christian and Nathan, and I had a penchant for set design, which always made the photos a bit different than most people’s expectations of the quintessential ‘surf family’.

Mainstream coverage of surfing further pushed the budgets of sponsorship, contest prize purses, travel, and global trade shows, and it was all fueled by images seemingly captured in a moment. Art amassed rolls and rolls of film, which needed to be expensively processed and painstakingly edited with cumbersome equipment and an encyclopedic knowledge of lighting and exposure that few in the surf world had mastered. The demand was insane, and Art was a master of his craft.

With vastly increasing advertising budgets, Art spent more time in the studio doing product shots and shooting surf action mostly when hired by companies who were booking boat trips or planning other exotic travels. Gone were the days spent on the beach hanging on the tripod for eight hours shooting Pipeline, hoping to get that perfect shot which might grace a cover and become an image seen around the world.

A small army of young photographers were now hoping to get ‘that’ shot. There were so many magazines and advertising opportunities and a steady stream of new faces vying for the images they captured to find their way onto the light tables of the industry’s photo editors.

With growth, there came many more restrictions and the freewheeling days of the recent past where the characters and interesting stories were sought after was quickly changing to become more ‘family friendly’. Companies whose slogans had been a demand to party were feeling the pains of meeting financial projections and the business-degreed new owner class knew their growth depended on ‘back to school’ sales.

Digital technology was also taking hold and the photographer’s expertise was being replaced by new cameras that were no longer dependent on film, careful lighting exposure, and expensive processing. These new point and shoot cameras democratized and demoralized photographers who had spent years perfecting their craft.

The cost of growth was felt across the entire landscape, as magazines and companies, whose advertising budgets had helped build photographers’ careers, were being sold to bigger players from outside the surf circle. The rock ‘n’ roll free wheelin’ spirit that had created a global phenomenon in search of the endless summer was replaced by corporate bean-counters who would pick profit over quality as their jobs demanded. The magazines were consolidating as companies became more prudent with product placement. Circulation was dropping as more consumers were migrating to the web.

During Art’s tenure with Surfer his photos would appear on 35 covers and would define the look and feel of what had become the global fascination with ‘beach culture’. It was, in the arch of history, a relatively short ride from the early beginnings of Surfer magazine in the ‘60s to the end of its reign in 2020, when its doors would be shuttered forever.

With the demise of print publications and a massive number of images now available for quick perusal online, the future of photography has changed. No longer are the photos on newsstands, coffee tables, and waiting rooms, or gracing the covers of big glossy publications that have the opportunity to speak to the collective consciousness and be imprinted in our memories forever. It’s now, point, shoot, next, as the images flick by on the small screens of our phones. The current state of mass media consumption has pushed the photographer to stretch for other means of making a living.

Art’s love for photography didn’t diminish as he turned his eye beneath the ocean surface, creating marvelous underwater landscapes and teaching the joy of photography to a new generation of young college enthusiasts. The beauty of the ocean and the rhythm of the tides were recorded in the immense catalog of images that Art created in his life. He was one of the greatest photographers of his generation and his work will live long in the memory, a testament to a time and culture captured by the eye of a true artist.

Photo: Jeff Divine

This story was lifted from the pages of Wavelength Volume. 264 – pick up your copy here or subscribe and get every magazine direct to your doorstep here.