From surf movie soundtracks to flamenco via Pink Floyd and Alby Falzon. An exploration of music and surfing with contributions from Mikey February, Lee-Ann Curran and Clovis Donizetti.

Photo: Thomas Lodin

Human beings have been making music for millennia (bone flutes from cave systems in Germany have been carbon dated to approximately 40,000 years old, while other instruments are potentially much older), instrumental rhythms and sung harmonies are as innate a part of human culture as the most basic forms of language and communication. From the regimented beat of war drums or marching bands to ceremonial songs marking love, birth and death, music often provides an elevated emotional response to the fluctuating rhythms of our lives.

Sport, or a version of it, seems to have been equally as omnipresent throughout ancient human history, evidenced by 15,000 year old paintings in the Lascaux Caves in France which are thought to depict human figures sprinting and wrestling. The two cultural practices would undoubtedly have crossed over through the millennia, beating drums would have provided the soundtrack to ancient wrestling matches while hi-energy dances would have blurred the lines between musicality and sporting endeavour. And so, from their ancient origins, contemporary iterations of music and sport are prominent pillars in our cultural landscape. But intersections between the two (outside of the obvious examples of rhythmic gymnastics, figure skating etc) are less easy to pin down.

Major sporting events regularly use musical sound bites to celebrate goals and points scored or as half time spectacles to attempt to validate exorbitant ticket prices. Chants from fans come in many different forms, from the war-like guttural expressions of followers of the Icelandic national football team to the, at times witty, at times offensive, terrace songs of premier league football teams, to the unofficial anthems of national rugby squads. Combat sportspeople and their distantly-related brethren, darts players, invariably walk out to adrenaline inducing pop or rock songs before attempting to rip each other’s heads off, or indeed to throw tiny arrows at a nearby circle. Surfing’s connection to music is, in many ways, more mysterious than these examples. To watch surfing in real time is an entirely unmusical experience, beyond the random squarks of nature, but to watch surfing as most of us now do, through surf movies or surf clips, is an experience absolutely enmeshed with musicality in a seemingly unique way.

Photo: Thomas Lodin

Examples of creative integration between surfing and music are relatively common nowadays, examples from across the wide variety of musical genres and surfing styles include the work of Australian musician and composer Richard Tognetti and Derek Hynd, most notably in their projects Musica Surfica and The Reef, as well as the compositions and live scores of CJ Mirra, a British recording artist and sound designer. While both of these musical figures might have some surfing experience, for this piece I wanted to gain insight from world class surfers who were also musicians or had recently produced work where the intersection between music and surfing was a key component.

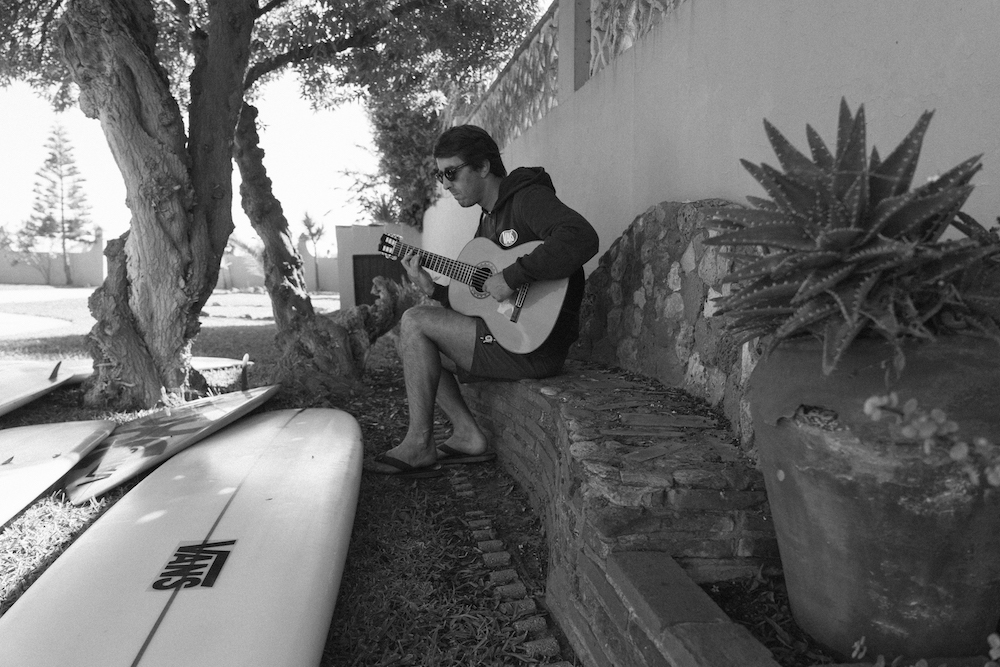

I was interested in finding out whether the music which was present in their lives, was also present when they surfed, and whether they were aware of a time when a specific genre of music or even song had changed their approach to a wave. During a clumsily organised yet insightful zoom interview (i’d like to think that I will learn from my mistakes but a calamitous pattern of technological mishaps is starting to emerge), I managed to talk to professional longboarder and musician Clovis Donizetti, musician, professional surfer and former World Tour Athlete, Lee-Ann Curran and another former World Tour surfer, stylistic icon and music lover, Mikey February.

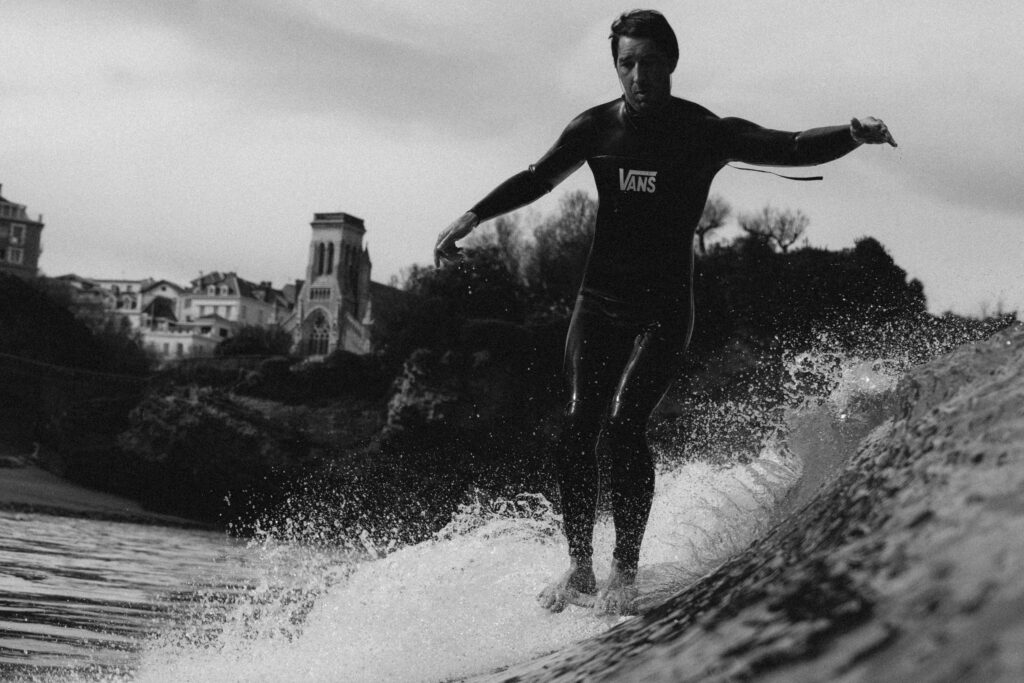

Mikey’s two-part series Sonic Souvenirs is an eclectic glimpse into the musical and surfing cultures of both South Africa and the Ivory Coast. It is a colourful, and indeed sonically magnificent, journey interspersed with conversations with local musicians who also contribute to the soundtrack. One such musician was Steven Amoikon who, on the cultural diversity of the Ivory Coast, said ‘there are 175 different types of ethnic groups in Ivory Coast, each of them has rhythms, each of them has dances.’ I asked Mikey about this quote and his experience of travelling the world through the lens of sound and surfing. ‘The music, the style, the rhythm is definitely different from place to place, whether that’s in the ocean or in the character of the people. When you go to these diverse places you really get a sense of what makes that country and the music and the people so unique, and that’s what we tried to get across in the film.’

Photo: Thomas Lodin

Sonic Souvenirs is indeed a vibrant celebration of African surf and music culture, but Mikey’s surfing was a constant throughout the varying mood of the series. His choice of manoeuvres, body positioning and navigation of often imperfect waves is typically his own even as the rhythm of the music changes. While Mikey is undoubtedly musically minded he is not a musician himself, perhaps a practical involvement in the crafting of the soundtrack was necessary in order to tune one’s surfing in a certain direction?

Photo: Thomas Lodin

Over the months which spanned the global pandemic, Lee-Ann managed to stitch together the brilliant surf film Cadavre Exquis. A collaborative effort from the female riders of the Vans surf team, the soundtrack of the film features several of Lee-Ann’s original compositions as well as contributions from some of the surfers themselves, including traditional Hawaiian singing from Pua Desoto and a song written and performed by Hannah Scott. Although she didn’t think any of the surfers in Cadavre Exquis surfed in a specific way for their part, Lee-Ann seemed excited at the prospect of doing so in the future, ‘I definitely explore a wide range of music.

What I listen to compared with what I surf to in films is a little different, it’s more fun music in films. I recently made a song with Hannah for a new video which is like nothing I’ve ever heard. So now we need to get good waves to go with the song. It’s cool because she has a really intuitive approach to music, maybe because she is a surfer…’ This reversal in approach to soundtracking a surf movie is something that Lee-Ann has done in the past, and is something that might be unique to the world’s surfer/musicians of a certain level. ‘Sometimes you have a song in mind then you have to surf in a way which enhances the song, it can work that way around too.’

Photo: Iker Baserretxea

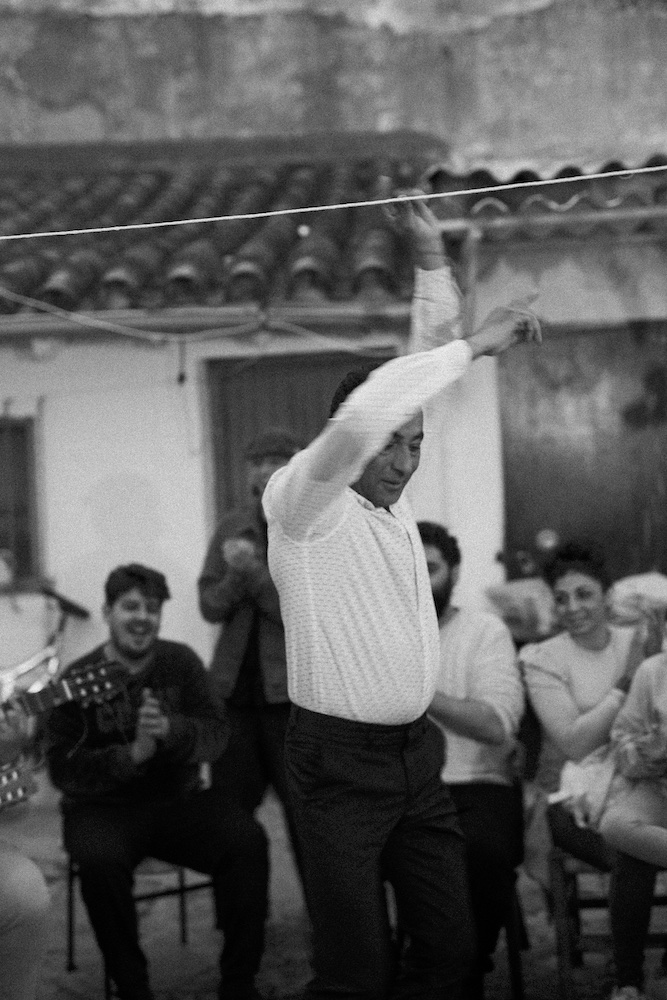

While Lee-Ann hinted at a direct relationship between her surfing and music, it was Clovis who had seen such a phenomena at first hand, while shooting his short film on flamenco and surfing, Con Duende (a phrase used in the world of flamenco, roughly translated as ‘bewitching’). Clovis had been immersed in the world of flamenco for many years, but his young co-star, Jules Lepecheux, had never experienced it before. In Clovis’s words, ‘Jules was the one who most felt the spirit of Flamenco. He had never heard flamenco until he came. There is a lot of meaning in the way you play the music and how you could use this to surf. On the second day we all went to this big party where we played with the flamenco musicians and they explained to Jules about the rhythm. From that moment on you felt his surfing just switch so that there was a completely different dynamic to it, or rhythm if you like. He was so excited I could almost hear the inner beat of the flamenco counting, you could see that he was tuned into it.’

It is a dramatic revelation like this which I had speculated might be present in all surfer/musicians, as if their musical leanings or current tastes would directly influence the way they rode waves. For the most part, this doesn’t seem to be the case, at least not in the way I had imagined. In Jules’s case, his experience as a drummer seemed to give him a short-cut into the rhythm of flamenco, a rhythm which gladly expressed itself through his surfing.

And perhaps longboarding itself is a form of surfing more open to the self expression of the surfer, less at the whim of the power of the wave. While my fantasy of hybrid art forms performed by polymathic surfers turned out to be just that, a fantasy, Clovis was on hand to remind me of the parallels which undoubtedly exist between the two art forms. ‘Surfing can be big waves, small waves, longboards, shortboards, dynamic surfers, slower surfers. And music can be the same, it can be three chords and roaring at you like Jules and his band or more sophisticated jazz playing or even you, Lee-Ann, with your harmonies which are more pop and complex. It’s what you want to express, and when you surf you don’t necessarily think about it like that, but it is possible to twist your surfing to whatever you want to express, you know? Like I would love to be able to surf on top of jazz and make my surfing as classy as Miles Davis’s trumpet but then I’ll always express my own thing at the same time. Everybody has their own thing that makes them unique, I can spot Lee-Ann’s surfing from far away, I can hear a guitar solo and know exactly who is playing.’

Photo: Thomas Lodin

It is in this idea of self expression where music and surfing can run side by side, and where the best surf movies manage to make them move as one. So it is to the central theme of Con Duende, and the title of the film itself, where we can look for the most succinct summary of the idea. In his film, Clovis says, ‘There is another aspect that fascinated me early on with the concept of “duende”, it is that Flamenco requires great technique (be it dancing, singing or playing), but that one cannot rely only on his technique, even a virtuoso. He needs that extra feeling, a sense of timing or, in other words, soul.’ In our interview he expanded on this idea of ‘duende’ with specific reference to surfing, ‘You can be a great technician but, in flamenco especially, someone might say, “well you don’t express anything.”

You never read a book and remark upon the alphabet used, the letters might be in the right order but if it doesn’t tell a story then it is just meaningless words. You can see someone who is surfing great but you can often tell that it’s very academic, there is no connection between the manoeuvres. It all works in the end but, personally, I’d rather watch someone who is expressing something, someone who has something to say when they surf.’

At last I am beginning to understand. There might not be literal music present in the best surfer’s performances, but the sense of self expression is there all the same. Tom Curren and Kelly Slater are not as successful as they are because they know how to play the guitar, but because they are expressing something beyond their consummate technique when they are surfing. The ultimate surf movie isn’t necessarily some futuristic project with waterproof headphones and live music (you heard it here first), or even some Hynd-ian project in the Western Australian desert with a string quartet strapped to the side of a cliff above a winding point break. It is the soul of the music and the soul of the surfing which combine to make great surf movies, those movies which have something to say beyond the formulaic, which are made with their own rhythm. That in flamenco might be said to be ‘con duende’.