A TALE OF RESISTANCE AND LOSS ON THE ROAD TO ERICEIRA

This article is lifted from the pages of Wavelength Vol. 263 and is always better in print. You can grab a copy of Vol. 263 here or subscribe for £25 a year, to receive both mags direct to your door along with a bonus freebie of your choice as a thank you for being part of the Wavelength fam.

Words, images & illustration: Alan ‘Fuz’ Bleakley

I’ve never thought of surfing as going to war with waves (‘rip-and-tear’, or ‘shred’). As somebody who started surfing prior to shortboards and now, in older age, exclusively longboards, I always saw surfing as an act of peaceful resistance.

Here, you transfer the energy of the wave to the board you are riding as an act of resistance to the wave’s dominant power. Ask yourself: how is it possible to hang ten without drawing the power of the wave into the resistant power that is the elegant riding of that wave? Such power shifts fascinate me.

As a person committed to social justice, I have always sought to challenge the custodians of repressive, authoritarian, or unjust regimes. This story plays on such themes. I recount a surf trip from 1970 where, in a small way, I challenged the repressive regimes of Spain’s dictator Franco and the legacy of Portugal’s ultra-conservative dictator Salazar who repressed the populace through a vicious secret police network.

My dad was dying. An untreatable pancreatic cancer had now spread throughout his body. The word ‘cancer’ is cognate with ‘crab’ – a creeping, jumpy creature that can retreat into its shell and linger, and then suddenly move sideways at speed, spreading its musk and devilry. He would die slowly over the next six months.

Post-university, I had been at home, in Newquay, to provide support for my mum. I had a girlfriend, Jenny, who I met at university. She had studied French and German and was keen to travel in Europe. My mum said that dad would last for another six months according to the doctors, so why didn’t Jenny and I go away for a trip? Jenny was keen to hitch around Europe, maybe France and Germany, for a few weeks during the summer of 1970. I suggested going to Biarritz so that I could surf.

We decided to backpack and hitch to Biarritz. Chris Jones made me a super-light 5’6” emerald green board. Soft round tail with a fixed single fin. I didn’t have a board bag and this was pre-leash days. We booked a night ferry from Dover to Calais (Plymouth to Roskoff did not get underway until two years later), stuck some maps in our bags, stuffed in a shortie wetsuit, wax, change of clothes, toiletries and a couple of paperbacks. That was the sum of our preparation. Not even a tent, rolls, or sleeping bags.

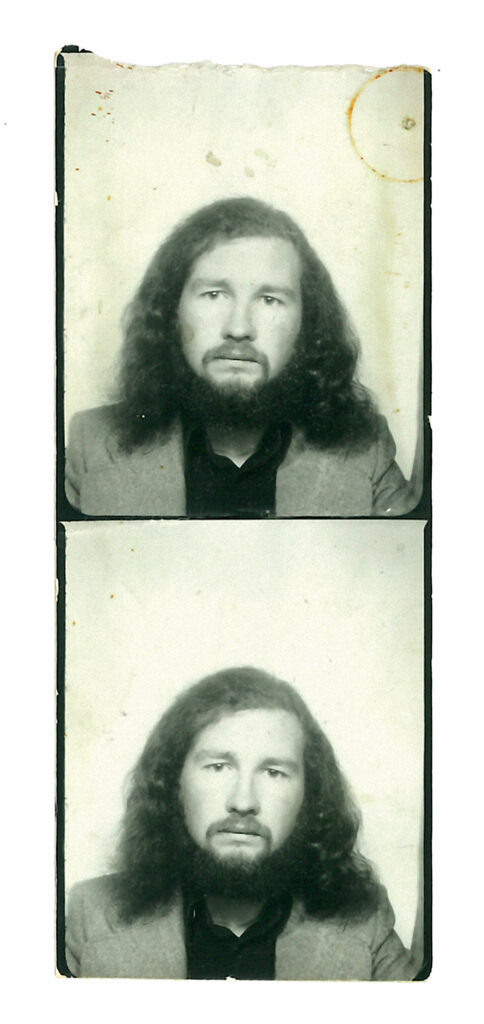

We got the packs on our backs, I got the board under my arm, we walked to the outskirts of Newquay and stuck our thumbs out. Logistically we were unprepared in four ways. First, hitching with a surfboard was difficult, however small. Second, we didn’t check whether hitching was even legal in France, it was not. Third, we had no contingency plan if we didn’t get any lifts. Realising that we wouldn’t get lifts in cars, we worked those thumbs extra hard to get lorries or vans to stop for us. Fourth, these were hippy days, we wore full denim and I had long hair and a beard. Did we even imagine that your ‘Ordinary Joes’ anywhere en route might not like long-haired hippies?

Oddly, getting to Dover was pretty straightforward. We rode in trucks and pick-ups, ‘Throw the board and backpacks in the back, and get in the cab.’ The crossing was smooth and we made it to Calais intact. Then the troubles started. At Calais, after sticking our thumbs out for over two hours, a gendarme approached us. Jenny spoke fluent French and charmed him. He told us it was illegal to hitch in France. We didn’t know this. Our luck had run out, or so we thought.

Serendipity: a truck came by and stopped, the driver curious as to what was going on, and an anglophile who often delivered goods to Dover. We explained the situation. He was driving to Paris, threw the board and rucksacks in the back and invited us into the cabin. The gendarme turned a blind eye as Jenny threw him a wink. We decided to spend a couple of days in Paris, found ourselves a friendly b’n’b and stashed our stuff. We did the tourist thing.

After a couple of days we were desperate to get out of Paris. Meanwhile, our thinking had changed. We wanted some adventure, and somehow going to Biarritz seemed a bit tame, a well-trodden path. I would probably only meet a bunch of surfers from Newquay there and we would hang out, a little Brit community. So we decided to take a risk. Over proper espressos with cognac, we pored over a map. Jenny suggested Portugal, ‘Fuck, why not?’. There must be surf in Portugal and seeing something of the country would be a real adventure. But having found out that hitching was illegal in France, we also discovered that it was illegal and dangerous to hitch in Spain and Portugal. We needed to get a train to Madrid and then change for Lisbon. From there, we could access the coast. Unknown territory.

It’s hard to imagine now but fifty years ago surfboards were an oddity. As I carried my stick through the streets of Paris to the metro, en route to Paris Gare de Lyon, every other person seemed to want to know what this strange craft with the ‘fish fin’ was. ‘Is it a boat?’ was the common question. Once at Gare de Lyon, we had planned to get a train to Madrid, and then change for Lisbon. But we first had to navigate the metro to the main station. We made our way down to the trains – only to be stopped dead by one of the ticket guys, who flung out an arm and even blew a whistle for our benefit. We showed him our tickets, but he wasn’t interested – he asked about the board and then said there was no way that I could take that on to the metro train.

Jenny’s fluent French and charm didn’t help. As we heard the train approaching the platform the guard pulled a metal mesh barrier about three feet high across the entrance. I thought on my feet and whispered to Jenny that as soon as the train arrived and the doors opened, I would jump the barrier and she must follow. We did just that, to the horror of the guard. It was a crush getting the board and ourselves into the train, but we got great pleasure from the look of incredulity on the guard’s face as the doors shut tight and the train pulled away.

Once at Gare de Lyon, everything went smoothly. We could only get tickets to Madrid – we would have to buy onward tickets to Lisbon once there – and the board was safely stowed in the bicycle carriage. We had to change trains at Barcelona. The journey took over 16 hours. We left Paris at around 8am and arrived in Madrid after midnight.

We had no idea where we could sleep, but just out of Madrid Atocha station was a public garden with benches. We sat up on a bench all night, dozing. It was warm, humid. Both of us must have dozed off. We were rudely awakened by prods in the side. Two policemen were standing over us with raised batons. Neither of us spoke Spanish and they couldn’t understand us, so we showed them our passports. They were not impressed or interested. We were arrested and they walked us to the nearest police station, where somebody did speak broken English and managed to make sense of the situation. Having made it all the way to Madrid, the surfboard at this point became an embarrassment. They were clearly freaked out by both my long hair and the surfboard – both of which they simply couldn’t place in their cosmology of known and tolerated objects.

The police took the board away and locked it up as if it were a criminal. It hadn’t even broken open a wave face, never mind a Spanish bank. We were told to hot-foot it out of Madrid as longhairs were not welcome. We explained, largely in French and broken English, that we were on our way to Lisbon. ‘Pick your boat up tomorrow’ they said. We were in no mood to argue. ‘And no more sleeping in parks or you will be taken to jail.’ They made us empty our rucksacks and meticulously checked our stuff. We made our way out and back to the railway station to get tickets to Lisbon. At least the board was safely stashed at the police station. Everywhere we went, people would stare. We felt like outcasts, strangers in a strange land, unwanted immigrants. Hospitality? Not in Franco’s Spain.

Now came the surreal part. After queuing for some time at a ticket office, the clerk refused to serve us. Someone behind us spoke English and intervened: ‘He’s saying there are no more trains to Lisbon today – come back tomorrow.’ That was ok, because we wanted tickets for tomorrow. We wandered a little and found a place to stay for the night, where we had to pretend that we were married to get a room together.

The following day, we had to pick up the board from the police station and get tickets to Lisbon. At this point, I was thinking maybe we should have stuck with our original plan and gone to Biarritz. We collected the ‘boat’ from some perplexed junior at the police station with twenty minutes’ worth of paperwork and a small ‘payment’ for its release. My beloved foam and fibreglass travelling companion was rapidly becoming somewhat of a burden. But I dreamed of waves ahead, and of less hassle than the day before at the train station. Dream on! We queued again, this time for a good half hour, with the usual strange looks – more at the surfboard than us. Finally, at the ticket office we managed to make ourselves understood, but the clerk waved his index finger, maliciously, ‘NO trains to Lisbon today!’ but we insisted, the departure board showed two trains to Lisbon that day. ‘NO trains to Lisbon today!’ came the reply. Under our breath we whispered nasty things and looked around in despair. The queue was getting restless. We needed help.

A small group of young Spaniards beckoned to us. Two of them spoke English well enough for us to understand. ‘This is Franco’s Spain’, they began, ‘you are hippie communists in their eyes and they will refuse you at every turn.’ Then they asked ‘do you have any Beatles records?’ We explained that the Beatles had broken up but promised to send them records when we were back in the UK if they could buy tickets to Lisbon for us. They agreed and we took the address of one of them and we did, indeed, send Beatles records when we got back home. Whether or not they arrived we would never find out, but the language of love had broken through. Half an hour later, one of the girls in the group came back bearing two one-way tickets to Lisbon. ‘I could not get you return tickets’, she said, we were elated nevertheless. Hugs all round and everybody smiling. ‘What about my surfboard?’ I asked, explaining to them what the board was all about and why we were heading for Lisbon. ‘Put it in the bicycle carriage and bribe the ticket inspector on the train.’ As a final gesture of thanks I gave our helpers a couple of Bilbo T-shirts from the rucksack.

Just to be sure, we checked with the first and only helpful platform attendant about taking the board on the train. He was insistent – we wouldn’t be able to do that ourselves. We’d have to check it in at the ‘freight’ department and they would make sure that it got on the train with us. If it had to go on another set of trains, as long as it was carefully labelled, we could collect it at the main station in Lisbon. We had to ‘pay’ (a bribe) at the freight office for someone to label the board with my name and ‘to be collected at Lisbon’. It all went pretty smoothly, or so we thought. We assumed the board would be transferred to the bicycle carriage in the same train that we were catching, but had no idea what would happen at the two changes en route to Lisbon. All I could do was hope and wish good luck to our faithful green companion, the ‘boat’. An hour later we were boarding for the long trip to Lisbon.

Safely in Lisbon, we made our way along the platform to the bicycle carriage – but, no luck and no ‘boat’. We tried ‘Parcels’ and ‘Left Luggage’ but alas, nothing. My heart sank. We found some overnight accommodation and trekked around Lisbon, a beautiful city with a mellow vibe in comparison with Madrid. We marvelled at the architecture and the pace of life. But still people looked at us with horror rather than joy. Despite being a cosmopolitan city, Lisbon was heavily conservative and Portugal, it seemed, was under an even stricter authoritarian regime than Spain, where the custodians of culture were the secret police. We found art galleries, museums and little cafés, some of which refused to serve us.

Over three days, twice a day, we visited the station where the ‘boat’ would surely arrive. Our talisman. In our small guest house, a lovely host had accepted us with open arms. She even saw through our ‘newlyweds’ ploy with a wink and a grin. She said she hated ‘the regime’. In a mish-mash of French and broken English, we asked her where we should go, close by, on the coast. She said ‘Go to Ericeira’, just a short bus ride away, ‘It’s quiet with beautiful beaches.’

The beautiful green board, unused, did not turn up. I never saw it again. This was to be a surf trip with no surfing. Rather, we had turned into small agents of resistance, challenging the custodians of repressive regimes simply by our (intolerable) presence. We arrived in Ericeira and found a guest house with a friendly host. It was quiet, sunny, uncrowded and the air was salty and fresh with a cooling breeze. The best beaches were a half-hour walk away along a partly unmade road that hugged the coast. We’d walk to the beaches every day and most days would get harassed, shouted at by passing locals in beat-up cars and trucks. We were spat at and on a number of occasions had small stones thrown at us. David Crosby’s song ‘Almost Cut My Hair’ was our anthem.

On the beach were just a few Lisbon-based tourists, probably with second homes in the area. The water was cold, so the shortie I had brought came in handy. I couldn’t help but compare the place to home in Cornwall. But what a cultural shift. Every day the same woman would wander up and down the beach with a big wicker basket on her head shouting ‘patatas fritas’ – big, delicious, greasy crisps. In her apron pockets she had bottles of water. There were never more than a handful of families on the beaches, little knots of people with picnic baskets. Everything seemed dirt cheap, but the guest house was really good with great food. Just another couple from Lisbon staying there who spoke enough English to fill us in on hair-raising tales of Portuguese politics. Ericeira is of course now a booming, bustling surf spot – a World Surfing Reserve. But it was first surfed regularly only in the mid-1970s. Who would have thought that 30 years later my son Sam would be competing on the European and nascent World Longboard Tours around Spain and Portugal? He won his first European title in 1999 just up the coast from Ericeira. In 1970 when sliver-slim shortboards ousted the old regime, we never thought that there would be a longboard renaissance mixing up traditional and radical styles.

Had my board turned up at the Lisbon station, I may have been the first person to surf Ericeira. It wasn’t to be. Instead, we became walking emblems of a ‘free’ lifestyle of longhairs. Ericeira was flat the whole time we were there. Middle of summer snooze and blues. Not a ripple. Had the board arrived, my perfect green 5’7”, I would have only used it as a ‘boat’. What an irony. There’s the rub: a surf trip with no surf. I contemplated cutting my hair for the return journey, but in the passage of time, over the next couple of decades, nature did that job for me with the creeping gift of baldness. After a near-idyllic week of sand, sea and ducking stones thrown from hippy-haters in crawling cars, we now had to get home. That’s another story of resistance.

Alan ‘Fuz’ Bleakley.

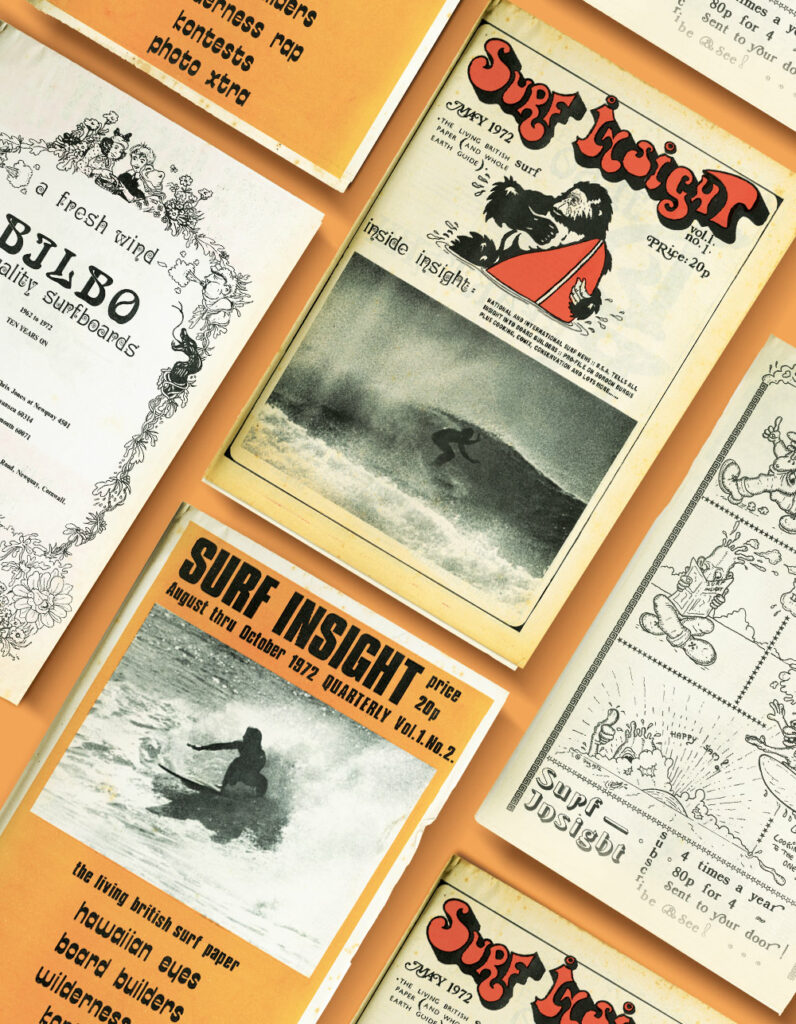

‘Fuz’ Bleakley, who has lived at Gwenver, West Cornwall, for many years, was amongst the first wave of surfers in Newquay. He got his first board in 1964 on his 15th birthday and has never looked back. He’s now been surfing for nearly 60 years. John Conway, a good friend, started Wavelength magazine in the wake of Surf Insight that Bleakley, Paul Holmes and Simonne Renvoize started in 1972. Bleakley designed decals, spray jobs, and advertising for John Conway Surfboards in the early 1970’s before he joined the mainstream as a successful academic. His son Sam was a multiple European longboard champion and on the world tour, and his granddaughters Izzy Henshall and Lola Bleakley are spearheading the next wave of British women’s longboarding.

This article is lifted from the pages of Wavelength Vol. 263 and is always better in print. You can grab a copy of Vol. 263 here or subscribe for £25 a year, to receive both mags direct to your door along with a bonus freebie of your choice as a thank you for being part of the Wavelength fam.