Twenty-twenty-one is Wavelength’s 40th year in print. To mark the occasion, we’re diving deep into our archive to bring you a series of short stories featuring key cultural moments, entertaining asides and colourful characters from around the British surf scene and beyond over the last four decades. Read part I here. Read part II here. Read part III here.

The series is presented by Oakley, who share our deep surfing heritage, having been equipping the world’s best with high-performance eyewear since ‘84.

Read more about the brand’s journey from niche cycling gear to beach cultural icon here.

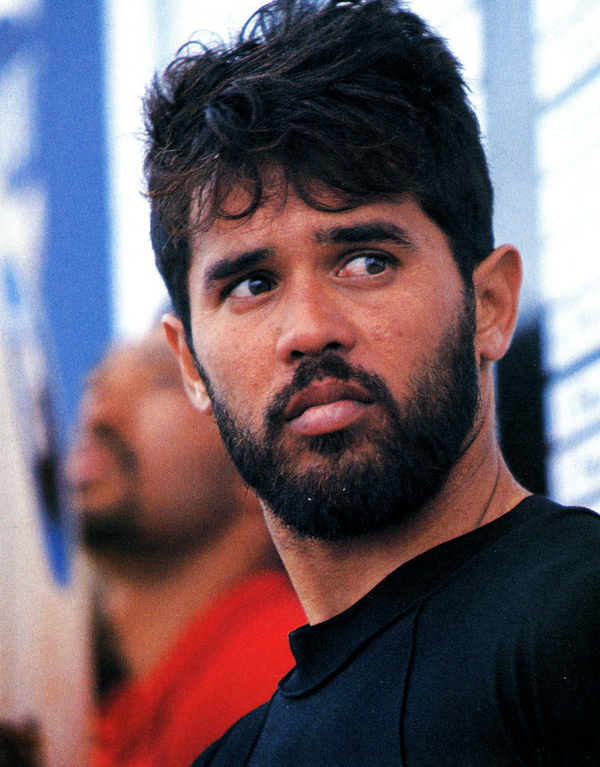

(1) Derek Ho and Pipeline formed one of the ’90s most iconic combos. Photo: Reef (2) From OG Micheal to second-gen Mason and Coco – the Ho dynasty continues to run deep on the North Shore. Photo: Joli

In 1993, Derek Ho became the first man to finally bring a surfing world title home to the islands where the sport began.

Born to a second-gen Waikiki Beach Boy in ‘63, Derek grew up in a low-income household, but one situated, as his mother Joeine liked to say, “in the lap of paradise.” Despite his natural talent and the close guidance of his older brother Michael, Derek seemed initially indifferent to forging a pro career, spending many of his formative years distracted by petty crime. However, after a short stint in a correction centre at 18, he was able to get his life back on track. “With a lot of help from my friends and family,” he told surf journo Steve Barilotti in a profile published in WL issue 48, “surfing finally turned me around.”

He joined the tour full time in ‘83, cementing his place among the top tier three years later when he scratched into what many called the wave of the decade on his way to his first-ever Pipe Masters victory.

“They’ll be talking about that one forever,” opined an incandescent Tom Carroll, clad in a dazzling pair of Oakley shades, who finished just behind Ho in the final that year in what would be the first of many closely fought heats between the two men at the spot.

After rising steadily to a second-place finish on the tour in ‘89, Ho’s fortunes took and turn and by the end of ‘92, he was languishing among the also-rans. The new school had arrived and were forcing their way up the rankings, spearheaded by Kelly Slater, who clinched his first world title that year. Many told Derek it was time to hang it up. He had plenty to be proud of. Seven years in the top 16. Three Triple Crowns. A Pipe Masters. But Derek didn’t quit.

In ‘93, he emerged, reinvigorated, with a string of impressive small wave performances to put himself in reach of a title going into the end of year showdown at Pipe.

In the semis, Ho faced up against his old adversary Tom Carroll, who was on his retirement lap. Tom was hungry to go out on a high, but as in ‘86, the Hawaiian had his number. Then in the final, Ho narrowly edged out Slater to claim his second Pipe Masters and lift the trophy as the island’s first-ever male world champ.

“The mantle of world surfing dominance had been returned to its ancient origins,” wrote Richard Johnston in WL issue 48, identifying this as the moment that the Hawaiians finally fixed the hinges on the door busted down by the Aussies two decades prior and re-asserted their rightful place on the global stage.

In the three decades since his victory, Derek’s elegant, unflinching style continued to inspire each subsequent generation of local chargers. He remained at the very top of the pile at Pipe, scoring some of the biggest, hollowest waves each and every winter right up until the day he died suddenly of a heart attack, aged 55, back in July 2020. He is greatly missed by the whole North Shore community, but as long as surfing still exists along the Seven Mile Miracle, will surely never be forgotten.

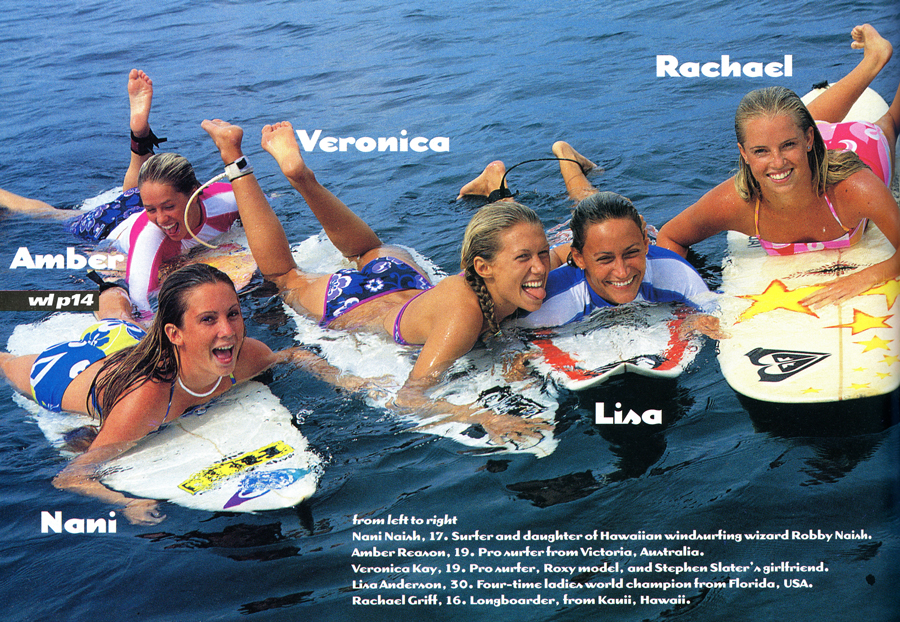

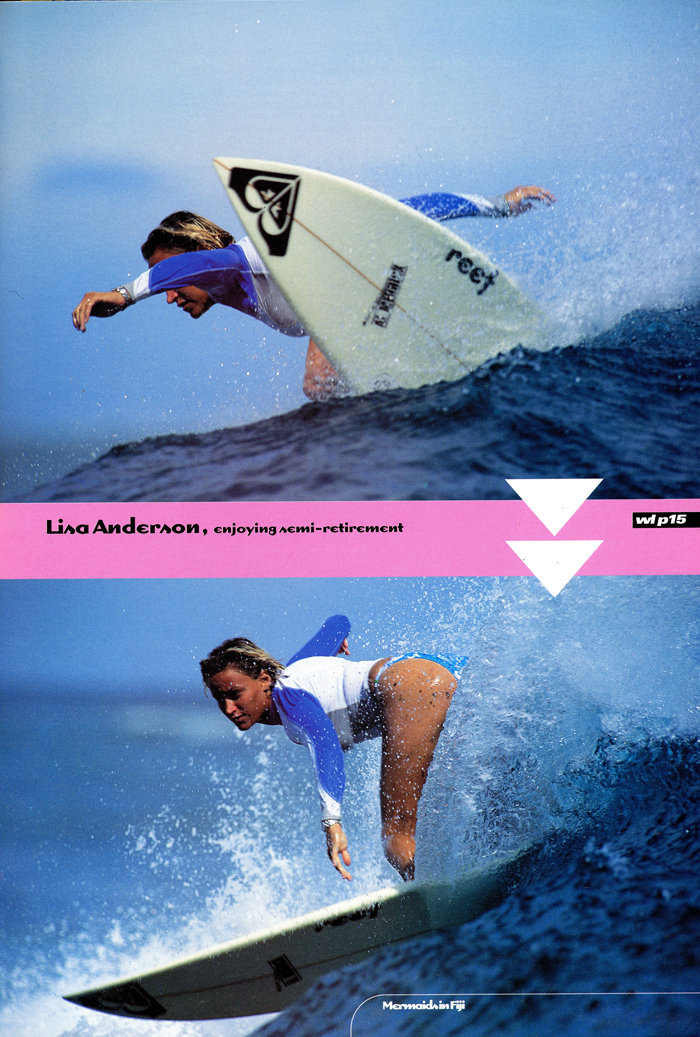

(1) Lisa, tubed in the tropics. Photo: Brian Bielmann // Roxy (2) Sporting a pair of Oakleys in the early ’90s. Frame from ‘Trouble’.

Like Ho – and most of the ‘90s most successful surfers – Lisa Andersen gravitated to riding waves as a way to escape the troubles of her youth. But unlike Ho, she was able to make it big, not because of her family and the place she was from, but because of her burning desire to get away from it.

At just 16, soon after her alcoholic father smashed up her first surfboard, she ran away from her home in Florida to start a new life. Arriving on the west coast, she waited tables, surfed non-stop and tried to stay out of the way of her abusive boyfriend. Eventually, she fell in with the crew at Aleeda Wetsuits who gave her the support she needed to kick off her competitive career. From that moment on, Lisa’s life features such a litany of defining cultural moments, it’s hard to know where to begin.

You could start with the day in 1990, when she won her first world tour event in Australia against world number one Pam Burridge (featured in Deep Cuts II). Or the day she was invited to join the Quiksilver and Oakley teams, alongside her heroes Kong and Tom Carroll, whose surfing she’d idolised and studied as a teenager in pictures torn out of a stack of Surfer Magazines rescued from her neighbour’s bin. Or the day in ‘96, when she became the first woman in 15 years to make the cover of that magazine herself.

Lisa leading a Roxy trip following her retirement from full-time competition at the end of the ’90s. Photos: Jeff Hornbaker

You could focus on how her talent and star quality inspired the creation of Roxy, opening a whole new chapter in women’s surf history. Or, the fact she essentially pioneered motherhood on the pro-tour, continuing to compete into her sixth month of pregnancy and only pulling out of the final event of the year when she turned up to Margies to find it breaking at double overhead. Of course, she didn’t stay out for long, returning to full-time competition just two weeks after the birth, with baby Erica on her hip. By the time Erica turned two, Lisa had clinched her first world title.

The media loved that story, especially because the pregnancy came as a result of an affair with world tour head judge, Renato Hickel. Over the years that followed, Lisa racked up a further three world titles and more media coverage than any female competitor before her. “Women’s surfing, as far as America goes, is Lisa Andersen,” said a resentful former world champ Pauline Menczer in a ‘95 interview with Matt Warshaw. “Nobody else really has an identity.”

However, soon the booming interest in female focussed surf fashion and lifestyle would begin to drag a host of rising stars into its orbit. For the rest of the decade, Lisa remained right in the middle of it; equal parts captain of the ship and figurehead at its bow. But, by the time she slipped off tour and into a role as an ambassador, coach and mentor, a hungry new generation of female surfers had emerged, ready to burst into the new millennium and smash through any glass ceilings they found when they got there.

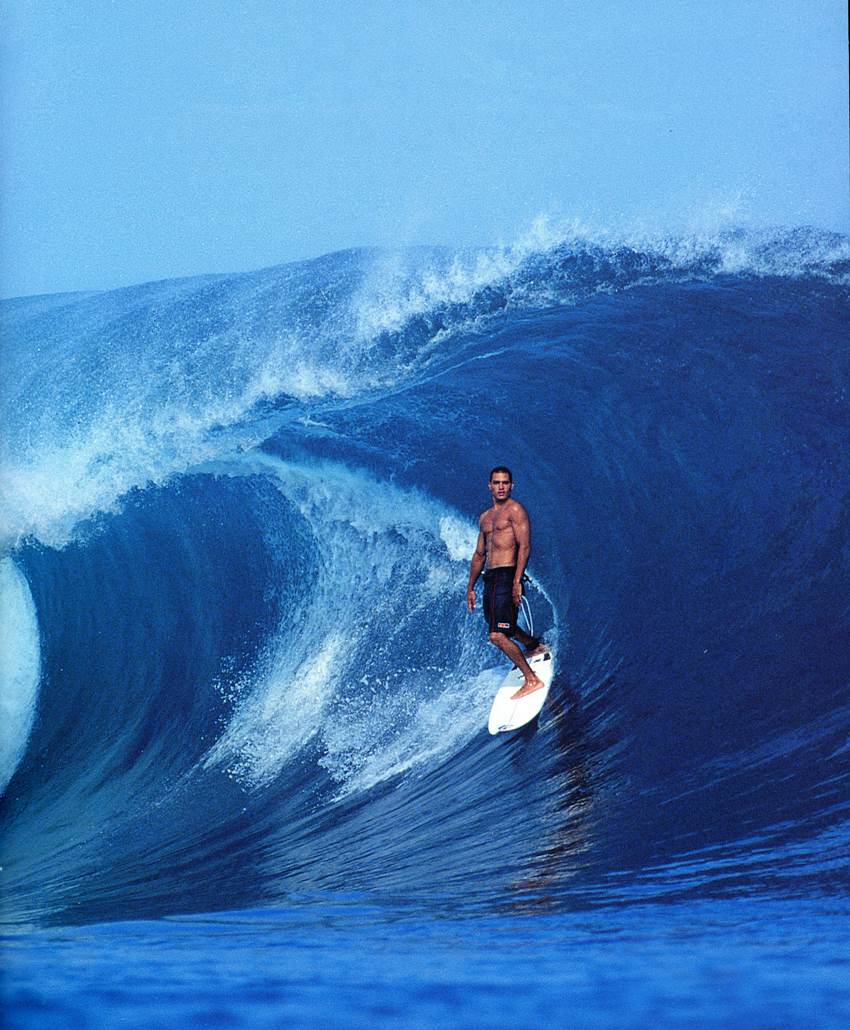

(1) Kelly Slater stood tall at G-Land. Photo: Jeff Hornbaker // Quiksilver (2) Prize-giving at the innaugral G-Land Pro. Photo: Joli

In the mid-90s there was a rebellion brewing on tour. Many of the competitors had had enough of surfing the soft, inconsistent city beach breaks that dominated the circuit. They appealed to the event sponsors, who up until then had been too obsessed by bums on the beach to consider taking the tour anywhere too remote. But in ‘94, Quiksilver answered the rallying cry with a radical idea. What if they staged an event at G-Land, the sparkling left-hander that spun for several hundred meters down Java’s southern tip, and then released the highlights from the event as a film? Not event coverage, with commentators and scores, but rather a highlight reel, with all the exotic cutaways and jangly psychedelic tunes of an actual surfing flick. The best surfers in the world at one of the world’s best waves.

“The logistics, of course, were staggering,” wrote Steve Barilotti of the build, “reminiscent more of the Burma hump operations of World War II than a surf contest.”

“Everything, down to the fax paper and paper clips, had to be shipped in… Teams of technicians, carpenters, electricians and labourers worked non-stop for nearly two months prior to the event building extra housing, hooking up power and installing radio-telephone communications. They also constructed two spacious multi-story platforms: one on the beach for journalists, the other tethered by cables halfway out on the reef for judges and photographers. Everything — generators, Jet Skis, computers and an incredible 1.5-ton sound system — was floated in over the knee-deep reef, off-loaded safari style, then rolled down the muddy paths via ox carts pulled by straining locals.”

For the event crew, the whole thing posed new levels of unpredictability. While shooting heats from the channel one morning, photographer Peter ‘Joli’ Wilson remembers his boat suddenly breaking down, leaving him and the local driver drifting helplessly out to sea. When he was finally rescued by a jetski and dropped off on land, he was flustered and eager to get back to capturing the action.

Fortunately, some Quiksilver execs had just been choppered in from Bali and their heli was sitting in a jungle clearing waiting to take them back, so, Joli jump aboard and whizzed up to capture some epic angles of perfect G-Land from the sky.

While the higher-ups enjoyed these and other opulent trimmings – cash flowed primarily by bourgeoning boardshorts sales at inland mega-malls on the other side of the world – for the surfers, the vibe at the G-Land camp was the same as it ever was. Heads were shaved, Bintangs drunk and out of tune guitars strummed awkwardly by introverted world champs. “You’d always bring a stash of goodies,” remembers Luke Egan of the antics that accompanied the first event. “And in the middle of the night, we’d go and put a bit of chocolate on someone’s lip and then they’d wake up with a rat running up their chest!”

The waves were as illustrious as hoped and in the end it was Slater who took out the comp with an incredible display of loose, fast carves and backhand tube riding. The GOAT’s career is too long and storied to call anything Peak Slater in good faith. But re-watching the footage now, that moment certainly feels close. Before wave pools, or injures or Instagram. Before ayahuasca or vaccine hesitancy. Just beautiful, era-defining surfing. “I’m just on overload right now,” he told Joli afterwards. “This is probably the greatest event I’ve ever won.” Adding that, if he retired right then and there, he’d be happy (marking perhaps the first chapter in what would become three decades of talking about retiring but not actually doing it.)

The response from both surfers and the viewing public, once the VHS landed in the shops a few months later, was resoundingly positive, emboldening the other big brands to stump up the cash to add their own slices of surfing paradise to the circuit. And so, the modern concept of the dream tour was born.

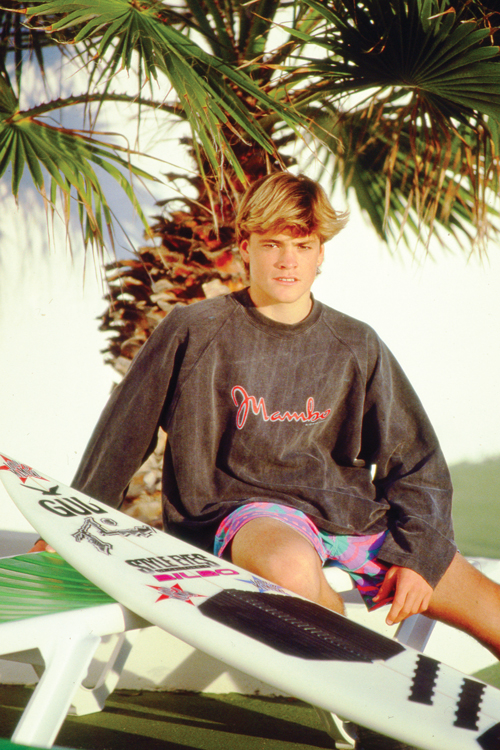

(1) 14 year-old Russ in Lanzarote. Photo: John Conway // WL Archive (2) On a tear at J-Bay. Photo: Tostee // ASP

Any compendium of British surf history, or tour underdogs, would be incomplete without a passage on Russell Winter – far and away the country’s most successful ever short boarding talent.

Born and raised in London, Russ moved to Newquay with his parents and two older brothers when he was nine. Landing on the Cornish coast was a bit of culture shock, as Steve, the eldest of the Winter bros, described in a 2003 interview with WL. “Where we grew up we would be walking home from school and some geezer would give you a headbutt,” he explained. “You had never met him in your life but he sees you walking down the street, wants a bit of aggro and he goes off.”

“When I came down here I always wanted to prove myself, if someone said something wrong to me then WHACK. I was not going to be picked on.”

As a result, Steve and the other boys attracted a formidable reputation from the moment they arrived. But, soon they discovered a perfect outlet for adolescent hot-headedness in the cold waters of the Atlantic. And once they did, it was all they wanted to do.

“Whenever we were at school we’d be trying to go surfing,” remembers Steve. “Mum and dad would take us to school and we’d all be crying in the car saying, ‘ah the surf’s perfect’ and mum and dad would say ‘ok, you can have the day off school as long as you go surfing all day’… they knew it was a sport we were taking a shine to.”

To maximise water time in the winter, they’d wake up at the crack of dawn, run down to Crantock or Fistral. Surf all day, only getting out for long enough to gulp down some food in their wetsuits. Then, when the light began to fade, they’d head to Harbour Left to surf under the faint lights of the pier. “Mum and dad would be sat up the top going f-cking kids, I can barely f-cking see them!” remembers Steve.

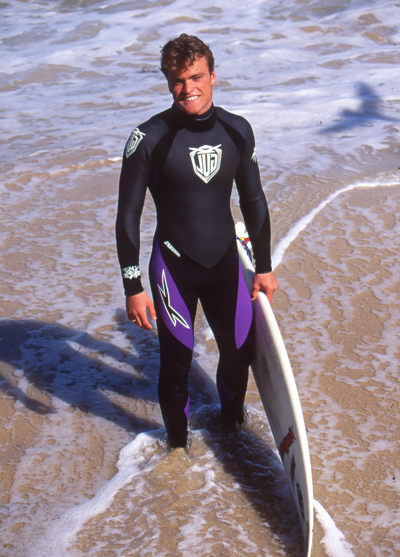

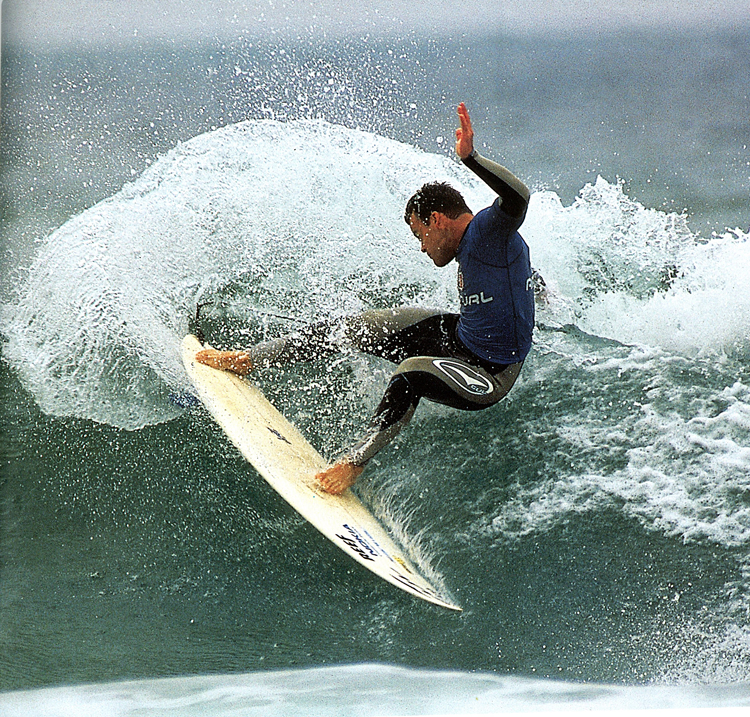

(1) North Shore floater from ’94. Photo: Phil Holden // Redley (2) Gul ad shoot. Photo: John Conway // WL Archive

That dedication paired with a natural ability saw young Russell quickly ascend through the junior ranks to the highest level of European surfing. Through his teenage years, he refined his small wave game and with the encouragement of his brothers during winters in Barbados, learnt to charge harder than anyone else in his age group.

At 18, he followed the likes of Carwyn, Spencer and Grishka to take a European title before setting his sights on the world tour. Three years later he qualified with an impressive eleventh-hour run on the North Shore. It was an electrifying moment for British surfing – to see a homegrown talent join the best of the best on the now fully-fledged dream tour.

Over the next four years, Russell would do the country’s surfing fans proud on numerous occasions, taking serious scalps including Occy at J-Bay, Slater at Sunset and Sunny Garcia on the Gold Coast. (“If I had half the heart that Russell did,” the Hawaiian would say years later, “I might have won a couple more world titles.”)

But it wasn’t all roses and Russell struggled with some parts of tour life – especially all the travel, thanks to a chronic phobia of flying. He also copped various injuries, including one sustained from an altercation with the reef at Teahupoo, which saw him almost forced to have his leg amputated. And, in later years, travelling alone as the sole Brit on a tour where many clubbed together with their countrymen, he reported bouts of severe loneliness.

By many accounts, tour life was a wild ride during the late ‘90s, with enough money and fame sloshing around to grease the gears of non-stop good times in beach towns around the world. In all the WL interviews we unearthed though, no one seems keen to ask Russ about that side of the tour. In fact, this is about all he ever said on the matter: “Let’s face it, you travel around the world all the time and it does get tiresome. If you don’t go out you’d get bored, sit in your room, you can’t watch tv, it’s French tv. So you go out and you have beers. People are getting drunk and it’s quite fun, let’s face it. There are loads of girls there, I’m only human.”

Although I’m sure readers would have relished tales of three-day benders in the tropics with Occy and Irons, for example, it didn’t much suit the image of what the tour was trying to portray itself as back then. The logic was: if it wasn’t good for sponsors and advertisers, then it wasn’t good for surfers and mags either, so everyone kept schtum.

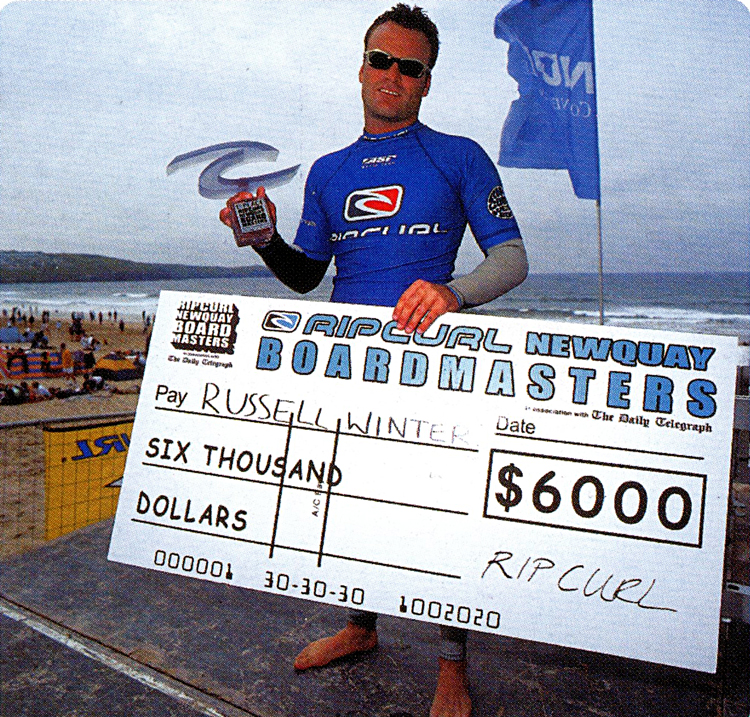

Claiming victory on home soil in ’02. Photos: Jim Michell // WL Archive

Despite never cracking the top 16 on the CT, in the latter half of his competitive career, Russ cemented his legacy with a series of victories and inspiring performances. Like in 2002, when he became the first and last Brit to win a QS on home soil, taking out the Boardmasters on the same Fistral peelers he first stood up on.

And an incredible wave caught at Teahupoo during that same year’s iconic event (won by Andy Irons), just a few years after his brush with the reef. Unfortunately, both took place in that historical blindspot before everything was uploaded to the internet and accordingly the footage is nowhere to be found online. Still, the story of these moments and more from Russ’ career live on vividly in local legend. Tales passed around in the pub and told to British groms as a touchstone of what they too could one day achieve. And maybe in a way, that’s far more powerful than a few pixelated Youtube clips.