This article is lifted from the pages of Wavelength Vol. 263 and is always better in print. You can grab a copy of Vol. 263 here or subscribe for £25 a year, to receive both mags direct to your door along with a bonus freebie of your choice as a thank you for being part of the Wavelength fam.

Words: Mike Lay

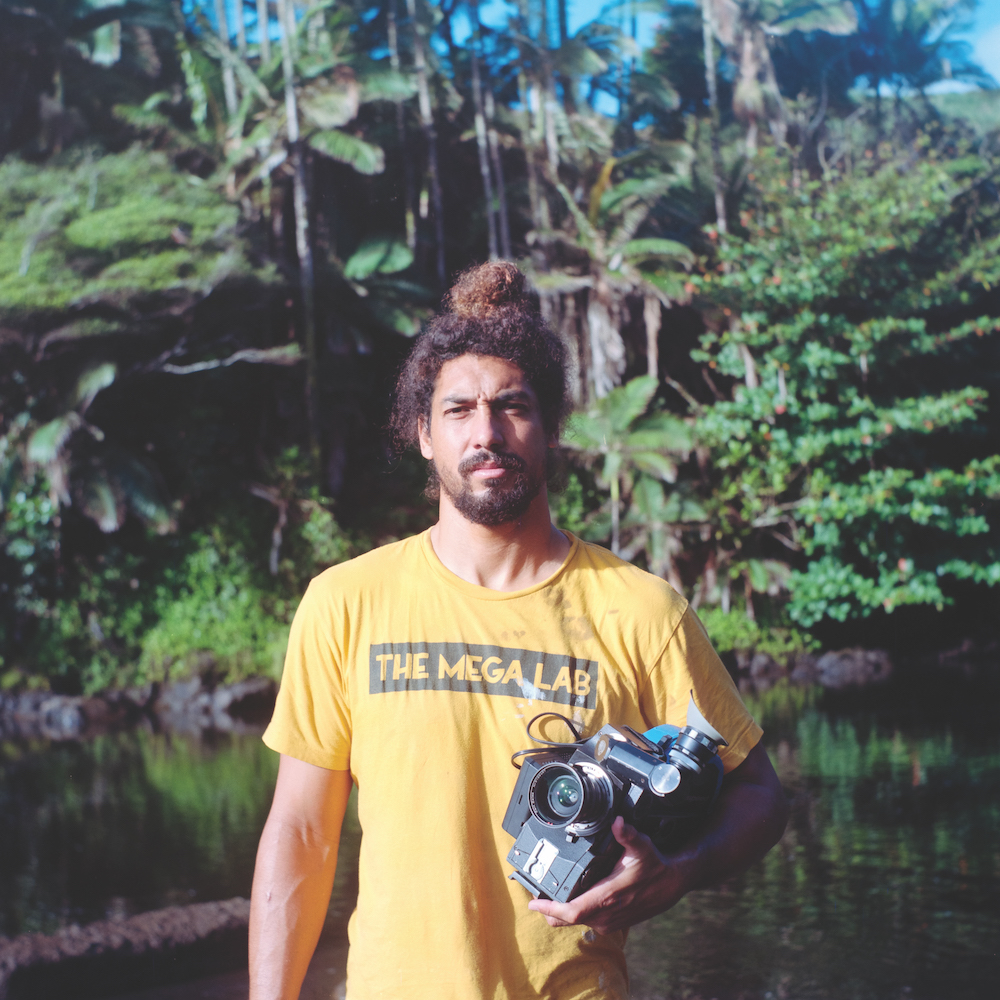

Our paths through life often seem set from a young age. Contemporary society likes it that way, in a world of intense specialisation there appears to be little room for those whose paths split into a multitude of directions. Dr Cliff Kapono is one who has defiantly confounded cultural expectations his entire life, as a PhD chemist and professional free surfer Cliff’s career has developed down two drastically divergent paths which he has managed to weave into one coherent journey. From the forests of inland Hawai’i through boarding school on Oahu, University in Southern California and the upstairs room of a coffee roastery in London (which is where our paths first crossed) to mapping the coral reef below the spinning lefts of Cloudbreak in Fiji along with his sponsor Reef, in this conversation Cliff maps out the fierce dedication and single minded intention which has lead him to where he is today.

I was already a few beers deep when I was dragged away from the magazine launch party. Climbing to the dimly lit upstairs floor to provide a stool sample to some chemist was not high up on my list of priorities that evening, but I trudged up begrudgingly. I now know that I was prejudiced before I ever met Cliff, incredulous at the idea that someone could be both a scientist and a surfer of any merit. My thoughts were in line with a pattern of confounded expectations which have surrounded Cliff throughout his career, from how a surfer should behave, to what a scientist should talk like, to how a Hawaiian should act in the water. In London, Cliff was gathering data for the Surfer Biome Project, a study aimed at identifying similarities between the gut biomes of surfers around the globe. As I filled out the accompanying questionnaire and chatted to Cliff I knew my initial reaction to him was wrong, he was clearly both a skilled surfer (just how skilled I would only come to realise years later) and a serious scientist.

But such a future was not at all clear to Cliff as a child growing up on the Big Island of Hawai’i where a combination of factors inhibited the slew of accolades which usually accompany professional-surfers-to-be. ‘I definitely wanted to be a professional surfer, I had that desire from an early age… but in school I wasn’t competing and we didn’t really have the financial support in my family to waste $20 a weekend on a contest. So I felt embarrassed if I didn’t make a ton of semis whenever I did do a contest. I always seemed to make it to right before the final round, and then the guys were just so good. Maybe I just didn’t have that extra competitive drive, or maybe understanding, or maybe ability. I don’t know, but I just couldn’t make it into many finals.’

Cliff’s inability to rise to the very top among his surfing peers was perhaps one of the reasons he was driven to succeed in science. He explains, ‘After having asked my aunties or other people in the community for money to enter, because I couldn’t ask my parents, and having told them that I could win, I’d be so embarrassed if I didn’t. Then I would go to my family and say, “Oh, I made top 10” in this or that Pro Am contest and my family would reply, “Oh, cool. How’d you do on your school work?” And I’m like, “I got A’s” and they’d be on the verge of crying they were so proud of me. So science became this valuable thing for our people, and that responsibility was kind of put on me, I was looking like I was way better at science than surfing. I was thinking, “What can I do to bring it back home? What’s more effective?” So I kind of decided, I’m gonna be a good scientist.’

Cliff was driven by the desire to make his family and his community proud and to follow his clear aptitude for science, but admits he always maintained a hunger to prove himself in the ocean too. ‘I was stubborn. I said to myself, “I’m gonna become a good scientist, but I’m also going to be a good surfer.”’

It might reasonably be assumed that Cliff took one path to completion then began on the other or at least invested more time in one or other of his chosen pursuits. From my own (far more elementary) experience of higher education, attending university left little time for my surfing addiction to satiate itself. While that was partly geographical (the Mersey isn’t known for its quality waves), my experience of surfing was limited to Marine Layer Productions and well thumbed magazines punctuated by once-a-month sojourns to North Wales or the East Coast. While Cliff was navigating the more testing waters of analytical chemistry all the way through to PhD level, he was achieving similarly staggering heights with his surfing. Cliff explains the deliberate parallels he drew between his formal education and his surfing education.

‘I decided that at High School I wanted to surf Pipe for the first time, then by my undergrad I wanted to surf Pipe on a good day. When I decided to get a masters I also wanted to start surfing Waimea. Then for my PhD in California I wanted to start surfing Mavericks. I just kept trying to keep it on the same level, thinking that maybe one day if someone were to say something to me like, “What do you know? You’re just a scientist.” then I could also prove myself in the water.’

Cliff’s surfing skill is abundantly evident to anyone who searches his name online. From high-fi performances on a regular thruster to timeless lines on twin fins and eggs to surfing Backdoor on an alaia. When he was living in Maui his surfing buddies included Dusty Payne and Clay Marzo whose performances he felt in touch with if not equal to. Despite this inarguable pedigree, it took meeting a Floridian surfing legend while studying in California for Cliff to truly believe he was good enough to hold his own in the surf industry.

‘Damien helped me believe in myself a little bit more. He helped me to know that I was good enough to surf wherever I wanted whether that was Mavericks, Todos Santos or Cortez Bank… And I treated that like passing my comprehensive exam, as if Damien Hobgood was my examiner and gave me the grade.’

When it came to his scientific career, a defining moment arrived at the end of the Surfer Biome Project when Cliff arrived back in California after travelling extensively in Europe collecting samples for his study. A seemingly unremarkable interview with a journalist about the project, initially for Men’s Journal, was eventually picked up by the New York Times instead. A turn of events which would thrust Cliff swiftly into the media gaze.

‘I’m so bad with those kinds of things, when they told me it was going to be in the Times I thought it was kind of like our paper the Hilo Union Review and I wondered if it would make it to Hawaii. I was like, “bra I don’t read that so i’m not going to see it.” And then it came out and it was like one of those movies where people are calling all the time and everyone wants to speak to me and do interviews.’

While the media attention was unfamiliar, Cliff quickly recognised a familiar pattern emerging in the interviews, a categorization he had worked his whole life to avoid falling into, ‘I was being seen as this scientist who likes surfing and that didn’t sit well with me. I didn’t want to be a gimmick. So I wondered if there was a way for me to be accepted as a legit surfer, one that has the athletic proficiency to participate in industry standard professional surfing. I wasn’t looking to be world champion or anything, but I just wanted that for myself you know? Can I obtain a degree in the scientific community? And can I have a contract in the surf community? And it ended up manifesting. That’s when I’m like, “okay, where do we go from here?”’

After a couple of smaller sponsorships, Cliff signed a contract with the global team of iconic footwear brand, Reef. Reef are currently funding a trip to Fiji with Cliff to map the ocean floor below Cloudbreak following a similar study of the reef at Pipeline, a ringing endorsement of Cliff’s achievements in both scientific and surfing domains.

Having achieved what he had set out to do in surfing and in science, Cliff looked to combine both of his skill sets as best he could. Given the nature of his twin pursuits combined with his affinity for the ocean, a trait innate to many indigenous Hawaiians, Cliff was often characterised as an ‘environmentalist’, a term that didn’t necessarily sit comfortably with him, but which did help him find a place in the, often insular, surf industry.

In a world sloshing with green wash and brands champing at the bit to announce their latest initiatives in the name of sustainability, Cliff is more cautious with proclamations of grandeur, while still ambitious as ever with his goals.

‘I’m not this eco brown Jesus that is going to save the planet from all the plastic, I know I’m not, I feel more like I’m an explorer. I’m searching for new spaces and new solutions and I believe that technology combined with indigenous wisdoms is an area which is unexplored. Just like my ancestors in their canoes exploring the physical world, I want to explore these different parts of our society.’

Cliff’s indigenous heritage is a fundamental part of his approach to ocean conservation and understanding. He insists there are parallels between indigenous Hawaiians who don’t surf and surfers without Hawaiian heritage, that both sets are better placed to have an insight into issues facing the ocean than the general population. ‘There are certainly similarities between being a surfer and being a Hawaiian. For example for a Hawaiian, no matter if they’re a construction worker, or a fisherman, or a hotel worker, we know this feeling of what it’s like to come from the land and from the sea. And that’s just innate, we’re born with it. It might not be obvious, some people might have the buzz haircuts and the earrings and the chains and everything, but I’m almost 100% certain that that person will see rubbish at the beach and get that dirty feeling. And it’s the same with surfers, you might love your big truck and your dirt bike and stuff but if there’s an oil spill, surfers feel it more than people who don’t have that connection to the ocean.’

While Cliff might see surfing as a pathway to a more profound connection to nature and indeed to place, he believes that it is accessible for everyone else too. He understands indigeneity to be within each of us, that we are all indigenous to somewhere but that the way we talk about indigenous peoples has become more mystical over time, celebrated certainly but also pushed out of reach of many who might benefit from a greater affinity to the planet. ‘Why is it so mystical to be a native person? I really don’t like that. I want to normalise the idea of being an indigenous person, and hopefully that will encourage other people to find their indigeneity from wherever they come from, because everyone is indigenous to somewhere.’

While in Ireland, again for the Surfer Biome Project, Cliff spent time with Fergal Smith on his farm in County Mayo. He remembers a lightbulb moment he had with Fergal which came to sculpt his ideas around indigeneity, ‘I was with Fergal on his farm and we were planting garlic. I was just helping Ferg and as we were putting them in the ground he said something like, “this is how we’ve done it for thousands of years.” And for some reason that phrase struck me, I turned round and looked at this freckly, blue eyed white person talking about his thousand year old tradition and it clicked. This is where he was from, his place, his culture, his language, it didn’t matter if he was white, black, brown or whatever. He was connected. I’m on that same level and to me, that’s the idea of spirituality and indigenousness, something which we can’t see, but which connects us.’

This willingness to look beyond traditional societal boundaries offers hope for a more connected future, surely a necessity if the human race is to survive in anything like it’s current form. It is also a feature of his latest project, MEGA Lab. MEGA stands for Multiscale Environmental Graphical Analysis and aims to provide a safe space for people to engage with science and the ocean environment regardless of the usual blocks to participation like background or academic pedigree.

As our conversation was coming to an end (well over the allocated hour and with half my questions still unasked), Cliff spun his camera to show me the room he was in. White walls, the sound of children calling, and a dense green beyond the square windows, a scene very much like my own. With characteristic generosity he offered his home to me and my family, if ever we were in Hawaii, and after we had said goodbye (and after dreaming for a minute or two of pacific islands) I reflected on the vast distances between us. The thousands of miles of ocean and continent, and the realistic unlikeliness of us ever being in the same room as each other again. But also reflecting on the remarkable similarities, that if one were to look at two versions of ourselves a thousand years ago that those similarities might have been even stronger.

So I am left feeling hopeful, that despite our massive differences in places of origin and upbringing (and me being terrible at science at school and 100% unable to surf Backdoor on a thin, finless plank of wood) we should have so much in common and to feel connected to. And that if we are to begin to act as responsible custodians of our homes, oceans and planet then that commonality is still there, still waiting to bring us together and to point us in the right direction.

This article is lifted from the pages of Wavelength Vol. 263 and is always better in print. You can grab a copy of Vol. 263 here or subscribe for £25 a year, to receive both mags direct to your door along with a bonus freebie of your choice as a thank you for being part of the Wavelength fam.