Like many of the bodyboarders who dedicated themselves to chasing the world’s heaviest waves in the early 2000s, Aussie Brenden Newton is no stranger to hairy experiences.

I first heard his name pop up in an account of the day Mickey Smith and a crew of fellow boogs first spotted Aileens, the now infamous big wave slab that breaks at the foot of the Cliffs Of Moher, way back in 2004. With no obvious way down the 700-foot cliff face, the boys decided to paddle from an entry point 4km up the coast. By the time they made it the tide had got too high, so they had to turn around and paddle straight back. “It must have taken them two or three hours,” recalls local bodyboarder Tom Gillespie, “and as they were paddling back it got dark, so they were using a lighter or a phone torch or something to guide them along in pitch darkness, at night, through ten-foot of swell.”

Photo: @lugarts

That episode would have been the crowning chapter in most people’s personal chronicles of gnar. But not Brenden. The story that takes that particular prize went down two years later, on the other side of the globe, and features a night at sea off Australia’s most treacherous stretch of coast and a wipeout that nearly cost him his face.

It all began for Brenden back in 2002, when he abandoned his university studies in medical science to pursue dreams of becoming a pro bodyboarder. Soon after, he met Mickey and took up starring roles in his seminal bodyboarding films ‘Against The Grain’ and ‘A Blank Canvas’. A few years later, Mickey encouraged Brenden to do his own film project, based Down Under, and in 2006 he set to work, recruiting lensmen and pulling together a crew of underground and up and coming bodyboarders for a series of missions to the nation’s heaviest waves. The goal was to make a feature film and fill an entire issue of Riptide Magazine with images and stories from the road.

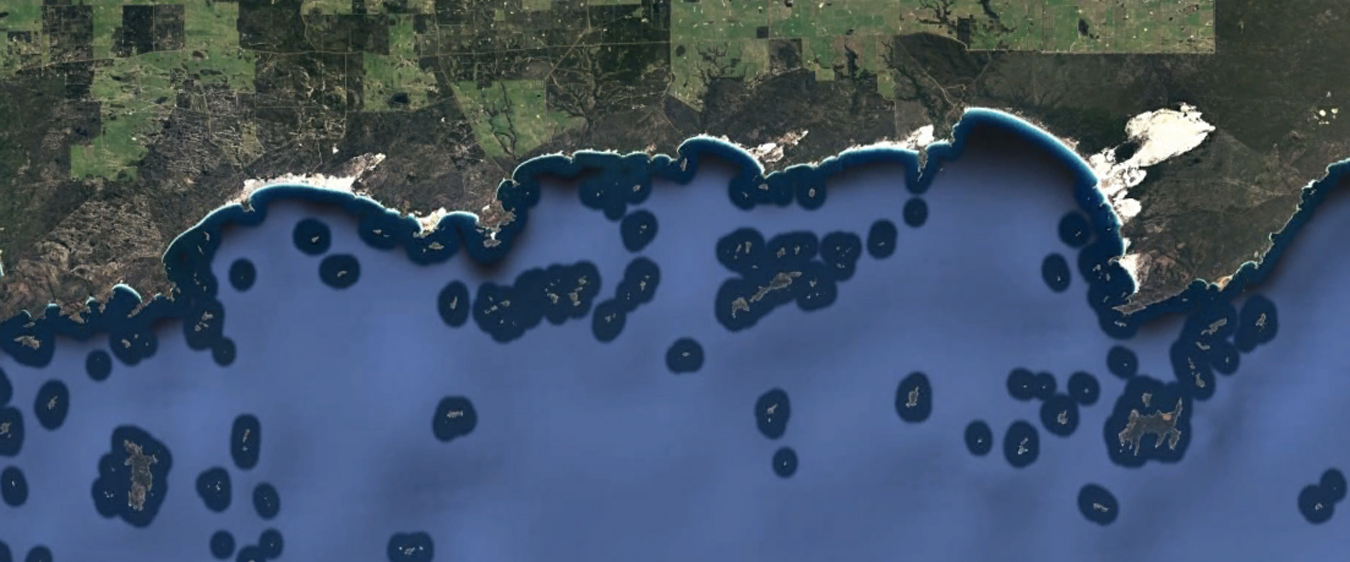

Image: Google Earth

As the deadline loomed, the crew spotted a solid swell heading towards WA and set off from the east coast to meet it. The drive took almost three days, without stopping. While one took the wheel, the rest of the crew slept across the back seats and in the footwell of their 4WD. Their destination was a stretch of deserted coastline near the south-westerly tip of the Australian mainland, strewn with slabs and offshore bombies breaking among dozens of tiny islands. As well as being hundreds of miles from help, the setups were as inherently treacherous as any on earth. Vast shelves of rock, covered in layers of knife-sharp 6-inch barnacles, lurching out of the deep with a diagonal gradient so steep many ran completely dry just a few meters in front of the take-off spot.

After spending a few weeks down there, a new swell appeared on the chart and the boys set their sights on a big day at Cyclops – a mutant, barely surfable slab, characteristic of the region.

The night before the swell was due, the group convened on a beach 40km up the coast. Between the six of them, they had a jetski, a 4WD and a 5-metre boat with an outboard and depth finder, but no radio or GPS. Really, concedes Brenden, it was the bare minimum required for seas as mighty as these, but back then it was all they could afford. The plan was to launch the watercraft that evening and motor down the coast to a sheltered bay near the wave where they’d meet the 4WD and camp for the night, before heading out again first thing in the morning. Brenden and Ryan Mattick launched the boat first, leaping uncomfortably high off the back of the incoming swell as they sped out towards the horizon. Once safely beyond the breakers, they sat and waited for the ski to join them. They were too far from land to see it launch – but they were sure the plan was to meet and go together. “We waited and waited,” recalls Brenden on the Grin Reapers podcast, “and I was probably over-loyal to them; I thought I don’t want to leave them. We’re going to go together.” By the time they realised the boys weren’t coming, the sun had already disappeared behind a thick layer of cloud on the horizon. As they set off in the direction of their camping spot, soon came the realisation there was no way they could make it before darkness fell.

Frames from ‘The Road’

“We knew roughly what direction what we had to go in,” continues Brenden. “But there are 104 islands in that archipelago – lots of them with slabs off the corners of them – that we had to navigate around to get to where we were going.” With a rising swell buffetting the boat and visibility to reduced to just a few metres in front of the stern, the situation looked bleak. Brenden describes the feeling as being akin to that of losing your parents as a kid; a sinking sense of dread that slowly engulfs you from the belly up.

A few dozen kms up the coast, a similar sense of worry was spreading over the rest of the crew. “The surf was so big,” recalls Glen Thurston, who’d arrived in the 4WD to the news that the others hadn’t made it. “I’d heard some stories the day before of a couple of guys that got lost out there fishing and nothing was found,” he continues. “They just disappeared.” The crew spent the next four hours driving up and down the coast, flashing their lights and beeping the horn. As hope dwindled, they sought out the park ranger, who in turn rang the authorities to report two men missing at sea. From there, the search and rescue operation began.

Out in the darkness, the boys were ploughing on as best they could. While Brenden steered, eyes fixed intently on vague shapes in the darkness, Ryan watched the depth finder, calling out when the number started to drop rapidly so Brenden could swing a right angle and hopefully avoid whatever island or slab lay just ahead. After narrowly avoiding a big surge of whitewash, the boys lost their bearings completely and total disorientation set in. Brenden in particular was extremely religious at that point in his life – describing himself on Grin Reapers as very vocal and compulsive in the way he practised his faith, with a reliance on God’s will looming large throughout the entire film project. However, he points out that in that situation, whether you’re religious or not, there’s nothing much to do but turn to a higher power for help. As the boys belted church songs loudly into the night, Brenden noticed a bright cluster of stars in the distance and felt compelled to go towards them.

“I fucking hate using that terminology now,” he says on Grin Reapers, “because it’s so abused.” But, at the time, with waves smashing the boat and islands lurking in the darkness all around them, it felt like the guidance from above he was looking for.

After half an hour following the stars, they began to feel the swell drop beneath them and eventually fade away to nothing. Exhausted and confident they’d found their way into a sheltered cove, they threw the anchor over, pitched a tent on the deck, stuffed down a few mouthfuls of tuna and crackers and – still in their wetsuits – curled up for the night.

Photo: Cookaa // Wikimedia Commons

A few hours later, dawn broke to reveal the grandeur of their surroundings; a narrow bay, backed by an endless expanse of mountains and dunes, flanked by two swell battered headlands. In the distance, Brenden spotted a 4WD parked up on the slope. He dived overboard and swam quickly to shore, finding the salty fisherman to whom the vehicle belonged and explaining their predicament. “Oh my god, you’re the guys everyone’s looking for,” said the fisherman, before leading Brenden to his vehicle and turning on his radio. “Two men missing at sea,” said the news reader’s voice. “Their friends have notified the rescue squad. The helicopters have been searching all night.” Brenden’s heart sank.

After collecting directions and a fresh can of fuel from the fisherman, they finally arrived in the bay they’d been headed for to find a full cavalcade of rescue workers lining the dunes.

“Well done,” one told them when as they came ashore. “We thought you were dead.”

It turned out boats and infrared aircraft had been out searching all night and by the sun came up, many had resigned themselves to what felt like the boys’ unavoidable fate.

“I’m not trying to be a fucking hero,” clarifies Brenden as he recounts the experience on Grin Reapers. “There’s a lot of collateral damage with those kind of stories. [My parents] were notified and they got together with my aunties and uncles. They’d been told it was pretty unlikely they were going to find us.”

Frames & clip from ‘The Road’

After sharing some reassuring words with loved ones over the satellite phone, the boys thanked the emergency services and soon, it was just the six of them again, surrounded by sand and ocean, reunited in their little makeshift camp. “We had a day just moping in the dunes. Regathering our nervous system,” remembers Brenden. That night they lit a fire and, as the swell continued to batter the reefs out the back, made plans for a mission the following day. They were going to finish what they’d started.

***

It was mid-morning by the time they spotted it. Brenden was huddled in the back of the boat when he suddenly heard the sound of hoots and screams cut through the roar of the engine. As they motored closer, Brenden saw the object of the crew’s excitement. Huge waves reared up and pitched onto a reef about the size of a garage, surrounded by deep water on all sides. “A big hole in the ocean, just imploding,” he says. They’d been checking various slabs and bombies all morning, but this was the first one with real promise and despite the obvious danger, Brenden knew he had to go. They were two days past deadline for Riptide and he was still without a cover. But it wasn’t just about the project. To stumble across a hitherto unsurfed wave in the middle of nowhere, just 48 hours after being lost at sea felt like destiny. They pulled on their fins and paddled out.

Photo: Luke Axisa

After a time feeling out the lineup, one by one, they spun and went, each getting chewed up on their first attempt by the barrel’s ravenous interior. Then, on Brenden’s second, he found the perfect line; a vertical drop, a few seconds hanging weightless on the foam ball and a boisterous ejection into the channel to howls of appreciation from the boat. “That was the best wave of my life,” he says, “from that moment on, I felt invincible.” Back on the peak, he searched doggedly for signs of an even bigger, heavier one, and when it came, he didn’t hesitate.

As the ocean drew hard off the reef below, the wave took on the form of a violent vortex and when the lip lurched forward, took Brenden with it, sending him freefalling into the trough. Barnacles tore at his arms and face as he was mowed along the bottom by the marauding whitewash. When he finally popped up and flopped onto the boat, he was covered in blood, with a hole in his cheek so big he could stick his tongue through it. It was a long 160km to the nearest hospital before he could be sewn back together.

Frames & clip from ‘The Road’

Reflecting on it now, 15 years on, the story is a perfect illustration of a moment when bodyboarders – at the time still largely written off by the wider surfing world – would go to incredible lengths to prove they were more than just a novelty act. Through the pioneering and often hopelessly risky exploits of Brenden and his ilk, the idea of what was surfable was re-defined and the way was paved for subsequent generations of prone and stand up riders alike to continue to push the uppermost limits of our sport.

In the end, Brenden got his story into Riptide just before it went to print and the photo from that wave landed straight on the cover. An account of the ordeal that led to it also formed the most memorable segment in the final film project – entitled ‘The Road’ – which remains a seminal ode to a chapter of wave riding history that will probably never be repeated.